Considering History: Protest Art and Art as Protest in American History

Art has been integral to the foundational American story of protest.

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

It’s hard to describe our current moment as a golden age for much of anything in America, but we are indeed amidst a renaissance of protest art. Portland’s inflatable resistance frogs have morphed into a consistent presence of life-size artistic costumes at protests, including at the massive #NoKings rallies on October 18th.

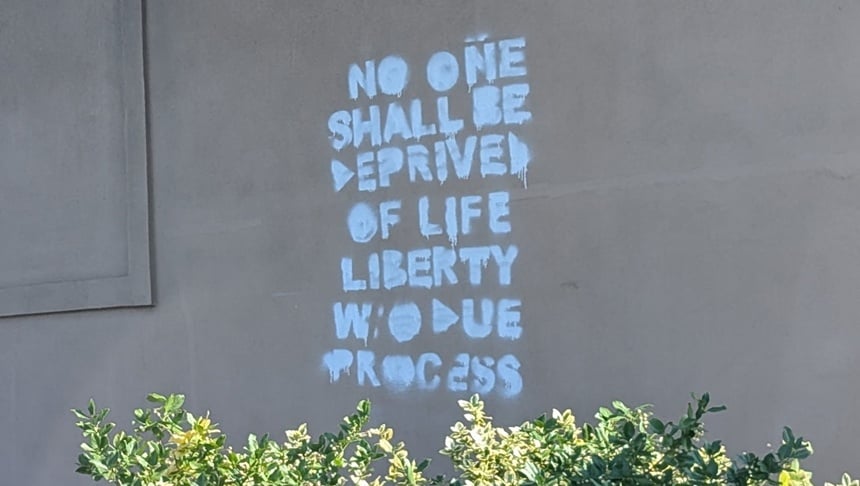

And public and street art has likewise become a consistent space for expressions of protest and resistance, as illustrated by this graffiti quotation from the 14th Amendment found on the wall of an abandoned Dunkin Donuts near my university in Fitchburg, Massachusetts.

Those examples comprise two distinct but interconnected categories: protest art — artworks present at or directly representing collective actions; and art as protest — artworks that themselves comprise an expression and form of resistance. Both types are part of a long, rich history, as art has been integral to the foundational American story of protest. Here I’ll highlight just a few examples of each category from across our history. (snip-MORE-click through on the title)

=====

Missing in History: Stagecoach Mary Broke Barriers (and a Few Noses)

America’s first Black female mail carrier defied bias, bandits, and bad weather to deliver the mail on time in Montana.

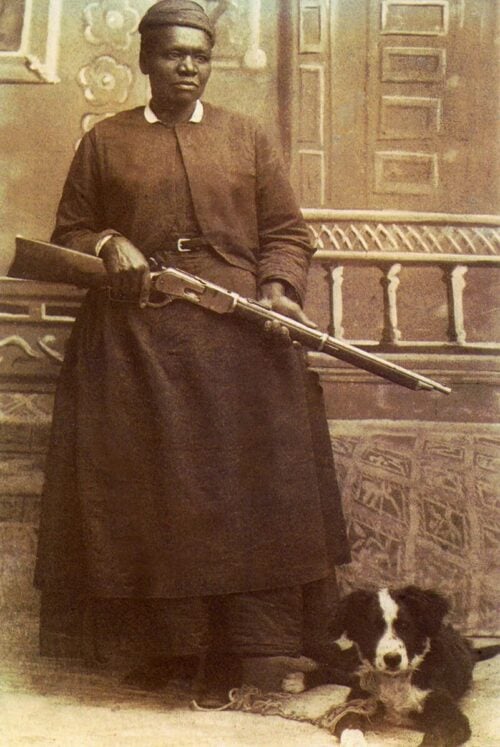

Mary Fields ca. 1895 (Wikimedia Commons)

“I like to be rough. I like to be rowdy. I also like to be loving….I like to baby sit.”

—Mary Fields

Mary Fields was as beloved as she was feared. Few people dared challenge the six-foot-tall, 200-pound former slave who carried a gun, drank, and had a hot temper. Despite her formidable image, Fields loved children, helped others, and carried the mail through the blizzards of northern Montana.

Born into slavery around 1832 in Hickman County, Tennessee and freed after the Civil War, Fields later found work as a chambermaid on the Mississippi steamboat Robert E. Lee. There she met Judge Edmund Dunne, who hired her as a servant in his household. After his wife’s death, Dunne sent Fields and his five children to live with his sister, Sara, or Mary Amadeus, Mother Superior of the Ursuline convent in Toledo, Ohio around 1874. There the former slave and the nun became fast friends. According to the Toledo Blade, legend has it that when Fields arrived in Toledo, Mother Amadeus asked if she needed anything, to which her friend replied, “Yes, a good cigar and a drink.”

The following year, Mother Amadeus was sent to Montana Territory to establish a school for indigenous girls at St. Peter’s Mission, west of the town of Cascade. When Fields learned that Mother Amadeus was stricken with pneumonia, she moved to Montana and nursed the nun back to health. After that, the 52-year-old Fields volunteered at the convent, hauling stones to build the school, fetching supplies from nearb y towns, washing the convent’s laundry, tending to its many chickens, managing the kitchen, and maintaining the mission’s garden and grounds. (While she lived at the convent, Fields refused to be paid for her work, preferring to come and go as she pleased.) (snip-MORE-click through on the title)