The Boy Who Accidentally Invented the Popsicle

120 years ago, 11-year-old Frank Epperson left his drink on the front porch on a chilly night. That accident became one of the most successful frozen dessert brands in the nation.

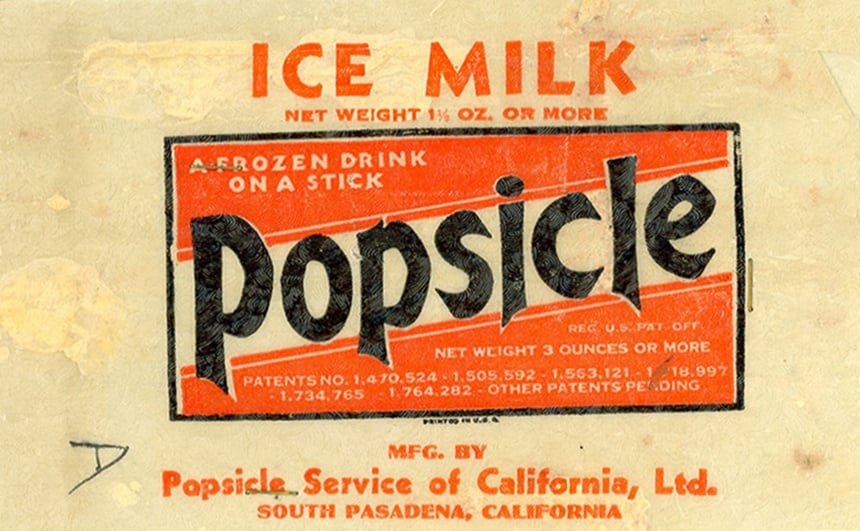

An early advertisement for Popsicle (National Archives)

Whether their favorite is ice cream, popsicles, or gelato, most people would agree that frozen treats are delicious.

While the origins of frozen desserts are unclear, they likely trace their roots back to the Ancient Persians, who used ice houses to produce and store faloodeh and sorbets. First-century Roman cookbooks included recipes of sweet desserts sprinkled with snow. Marco Polo is (probably falsely) credited for introducing frozen desserts to Italy after his travels in China, and Thomas Jefferson popularized ice cream in the United States — his handwritten vanilla ice cream recipe from the 1780s was one of the earliest in the nation.

But one story in frozen dessert history stands out, and it is not about a United States president or a Silk Road explorer: It’s about an 11-year-old boy.

On a winter day in 1905, young Frank Epperson made a beverage mixing soda powder with water to stay hydrated. One night, he accidentally left his cup on the porch overnight with a stirring stick inside, according to popsicle.com. Temperatures dropped during the night, and the next morning, Epperson found his cup where he had left it, no longer liquid, but now an icy snack. He ran the cup under hot water, pulled it out using the wooden stick, and tasted the new frozen dessert. He named it the Epsicle — a combination of “Epperson” and “icicle” — but unlike the process of its invention, the product didn’t turn into a national success overnight.

Epperson continued making Epsicles for his friends, and later, his children — who began calling the treat “Pop’s Sicle” or “Popsicle,” the name the brand keeps to this day — for many years. He also sold popsicles around his neighborhood until 1923, when he decided to expand his market to Neptune Beach — known as the “West Coast Coney Island” — where it became a beloved treat, selling as many as 8,000 in one day.

Following this popularity, Epperson applied for a patent on June 11, 1924, describing the Popsicle as a “frozen confection of attractive appearance, which can be conveniently consumed without contamination by contact with the hand and without the need for a plate, spoon, fork or other implement.”

Epperson’s request was approved two months later, and he immediately sold all of the rights to the invention that had defined much of his life to the Joe Lowe Co., which later started a subsidiary called the Popsicle Industries. Epperson later regretted the loss, saying: “I was flat and had to liquidate all my assets. I haven’t been the same since,” according to NPR. The frozen dessert brand, however, continued on without him.

A few years later, the Great Depression began to weigh heavily on the American public. As the stock market crashed and employment declined, struggling families had to cut out the ten-cent popsicles from their purchases. In response, the Popsicle Corporation devised the first two-stick popsicles so that two children could enjoy a snack for the price of one. According to a 1931 advertisement, “People who could not afford dimes, quarters and halves for ice cream gladly bought Popsicles at a nickel each for children, family and friends.” The two-stick popsicle became a huge success, doubling the company’s sales in a year. The Popsicle Corporation later declared itself “Depression Proof.”

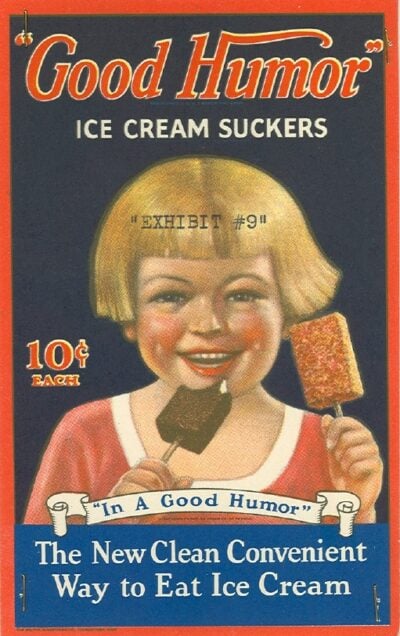

But not everything was as sweet as the dessert itself for the Popsicle brand. The Popsicle Corporation also had rivalries with the company Good Humor — a brand known for their chocolate-coated bars and the first ice cream trucks. The dispute resulted in a series of court cases over patent violations. The initial conflict ended with a compromise: The Popsicle Corporation would sell iced treats with no milk, and Good Humor would sell products containing milk. However, with the drop of dairy prices in 1932, Popsicle ignored the agreement and decided to tap into the ice cream market — coming out with a “Milk Popsicle” that included 4.48 percent butter fat.

Good Humor filed a lawsuit immediately. Both sides fought to define “sherbet.” Good Humor strictly defined it as “flavored water ice,” but Popsicle rebutted, claiming that most state regulators did not categorize the Milk Popsicle as ice cream, but with terms such as “imitation ice cream,” “frozen custard,” “milk sherbet,” or “ice milk.” The judge ruled for Good Humor, and both companies signed their new court-approved agreement on April 7, 1933. Ironically, over the next six decades, Unilever — one of the largest global consumer goods companies — bought the rights to both Good Humor and Popsicle, ending the Cold War between the two companies.

If you remember buying a cold treat from a neighborhood ice cream truck on a hot summer day, eating a Firecracker during a Fourth of July party, or splitting a two-stick pop with a friend, you’re one of millions that probably has nostalgic memories of Popsicles. It continues to be one of the most popular frozen dessert brands, and for that, we have an 11-year-old Frank Epperson to thank.

I never knew. What a story. I will share with others. In fact, I just related it to my wife. Cheers

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers!

LikeLiked by 1 person