Many names in this story. You can listen to it on the page; it says it’s a 22 minute listen.

The erotic poems of Bilitis

A lush translation of this late-discovered lesbian poet added to the legacy of Sappho, but there was a trickster at work

In 1894, a German archaeologist named Herr G Heim made a groundbreaking discovery. On the island of Cyprus, he excavated a tomb that belonged to a hitherto unknown ancient female poet by the name of Bilitis. Carved on the walls surrounding her sarcophagus were more than 150 ancient Greek poems in which Bilitis recounted her life, from her childhood in Pamphylia in present-day Turkey to her adventures on the islands of Lesbos and Cyprus, where she would eventually come to rest. Heim diligently copied down this treasure trove of poems, which had not seen the light of day for more than two millennia. They would have remained little known – accessible only to a small, scholarly audience who could decipher ancient Greek – had a Frenchman named Pierre Louÿs not taken it upon himself to hunt down Heim’s Greek edition, hot off the press, and translated Bilitis’s poetry into French for a broader reading public that same year (published as Les Chansons de Bilitis or The Songs of Bilitis). Bilitis might have been an obscure historical figure – no other ancient author mentions encountering her or her poetry – but the cultural and literary significance of Heim’s discovery was not lost on Louÿs. For, in several of her poems, Bilitis revealed that she crossed paths with classical antiquity’s most renowned and controversial female poet: Sappho.

Sappho (c630-c570 BCE) lived in the city of Mytilene on the island of Lesbos, where she composed lyric poetry – songs performed to the accompaniment of the lyre. Her poetry was widely admired throughout antiquity. Plato dubbed her ‘the tenth Muse’. In the 1st century CE, the Greek philosopher Plutarch recalled listening to Sappho’s poetry performed at symposia – wine-drinking parties – remarking that her words were so beautiful, he was moved to put his wine cup down while he listened.

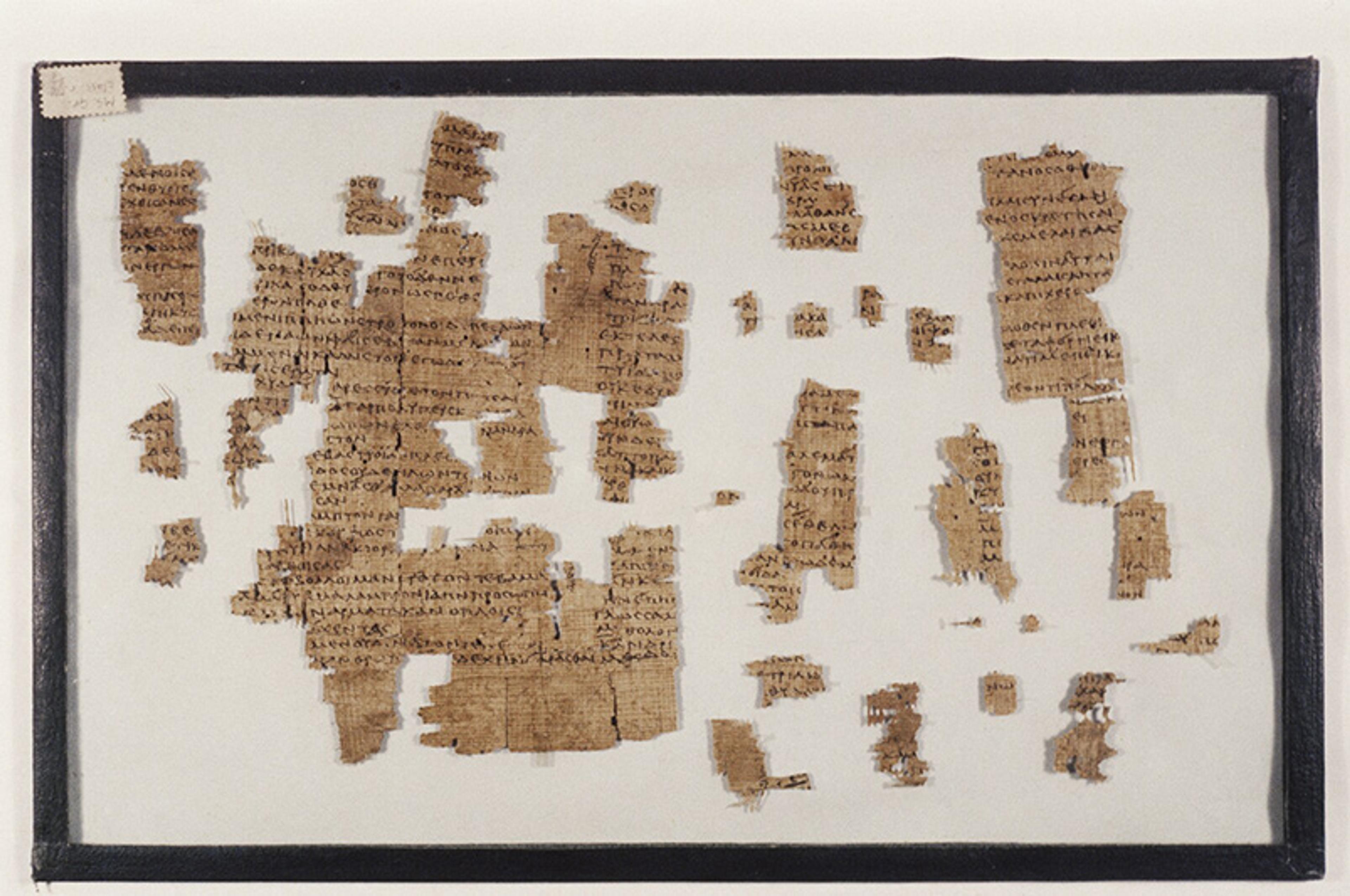

Sappho was significant enough to have her work copied by scholars at the Library of Alexandria a few hundred years after she lived – the same scholars who first systematised Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey into the books we are familiar with today. Of the nine book rolls of Sappho’s work these scholars produced, only a sliver survives. There is one complete poem, the so-called ‘Hymn to Aphrodite’, in which Sappho prays to the goddess of love to bring a female lover back into her good graces. The rest are scraps. Our knowledge of her poetry relies largely on papyrus fragments and partial quotations from later authors. As the classicist Emily Wilson put it in the London Review of Books: ‘Reconstructing Sappho from what remains is like trying to get a sense of a whole Tyrannosaurus rex from one claw.’

Among these precious fragments, we find some of the most stirring and exceptional representations of desire in all ancient Greek literature. In fragment 31, for example, Sappho sees a man sitting across from a woman and listening to her sweet voice and lovely laugh. She compares him to a god, but then this man, ‘whoever he is’, quickly fades to the background, and Sappho spends the rest of the fragment expressing in hair-raising detail the effects that beholding this woman has on her:

… oh it

puts the heart in my chest on wings

for when I look at you, even a moment, no speaking

is left in me

no: tongue breaks and thin

fire is racing under skin

and in eyes no sight and drumming

fills ears

and cold sweat holds me and shaking

grips me all, greener than grass

I am and dead – or almost

I seem to me …

(All translations of Sappho by Anne Carson)

Passionate desire, what the Greeks called eros, is no trifling matter for Sappho. In fragment 130 , Sappho calls eros the ‘melter of limbs’ who habitually stirs her, a ‘sweetbitter [glukupikron] unmanageable creature who steals in …’ If we are accustomed to think of love as bittersweet, Sappho inverts this: eros starts off sweet (gluku) but turns bitter (pikron), as some distance or barrier often comes between Sappho and her female loves, as in fragment 31 above.

We find expressions of the devastating stakes of eros among male lyric poets, too, but in those contexts, the poets sing of desire for beautiful male youths or ‘beloveds’. In classical Greek culture, this form of male homoeroticism, known as pederasty, is elevated as the most admired, virtuous, manly form of love, even superior to heterosexual relations. From our earliest Greek literary sources onwards, women’s desires and bodies are problematic. According to the poet Hesiod, Zeus invented the first woman – Pandora, a ‘beautiful evil thing’ – as a punishment for men. Her opening of the jar – not a box but rather a pithos, a giant storage jug as big as the human body – symbolises the misogynist view of women as leaky containers whose insatiable appetites, whether for food or for sex, must be controlled and regulated by men.

poem titled ‘Types of Women’, by Sappho’s contemporary Semonides of Amorgos, showcases this strain of misogyny on steroids. The poem attacks women through the form of a catalogue, listing different types of women and the animal-antecedents to whom they owe their shameful, negative traits. The only acceptable type of woman Semonides describes is the bee-woman, the ideal wife who directs her desire entirely towards enriching her husband’s household by bearing him legitimate children. This ideal woman never so much as mentions sex when in conversation with other women.

In comparison with this misogynist tradition, Sappho’s representation of women and desire could not be more different. Take fragment 16, which opens thus:

Some men say an army of horse and some men say an army on foot

and some men say an army of ships is the most beautiful thing

on the black earth. But I say it is

what you love.

In these lines, Sappho articulates an expansive vision of beauty. She lists the different kinds of armies that men find the most beautiful, using the form of the catalogue to invoke Homer’s Iliad, a war story whose plot and heroic values are underpinned by the violent exchange of women as property between men. Sappho does not tell us whether or not she thinks armies are beautiful. She simply says that the most beautiful thing is what(ever) we love (and therefore subtly claims that men think armies beautiful because they love war).

Sappho recreates through memory a single person who is beautiful because she is loved

She then explains her point by citing the example of Helen, the wife of Menelaus, on behalf of whom the Greeks fight the Trojan War. Accounts differ as to whether Helen sailed to Troy willingly to be with the Trojan prince Paris or was forcibly taken. Rather than castigate Helen as the epitome of evil – female desire – as most traditions do, Sappho simply states that she left behind her husband, children and parents, and sailed to Troy, because something (the poem is fragmentary; perhaps desire itself?) led her astray.

The point is this: even she who ‘overcame everyone in beauty’ pursued what she found the most beautiful thing on earth, what(ever) she loved. And this, Sappho says, reminds her of a woman named Anaktoria, who is gone. Sappho says:

I would rather see her lovely step

and the motion of light on her face

than chariots of Lydians or ranks

of footsoldiers in arms.

For Sappho, the beauty of armies pales in comparison with the beauty of Anaktoria because Sappho loves Anaktoria. ‘Ranks of footsoldiers’ behold women as exchangeable, dehumanised objects of beauty, not love. Sappho recreates through memory a single person, Anaktoria, who is beautiful because she is loved. What makes Sappho’s articulation of eros so exceptional, then, is how she challenges the dominating, misogynist attitudes about women and their desire as expressed by the male-authored Greek literary tradition. As the classicist Ella Haselswerdt writes in ‘Re-Queering Sappho’ (2016):

Sappho’s fragments show us eros and pleasure for their own sake, not as an exchange of property, the exploitation of one for the sake of the other, or in order to achieve virtue in the eyes of a moralising philosopher like Plato or Aristotle.

From antiquity onwards, however, Sappho’s expressions of lesbian eros attracted a medley of misogynistic and homophobic responses. In the 5th century BCE, following the tradition of pathologising women’s desires (whether homo or hetero), Athenian comic playwrights transformed Sappho into the stock character of a sex-crazed woman, insatiably hungry for men. In his Heroides, a collection of literary letters in which female heroines express their grievances to the men who have mistreated them, the Roman poet Ovid composed a letter in Sappho’s voice. His version of Sappho claims that her love for a young boatman named Phaon surpasses the thousands of loves she has had with girls on Lesbos. The ancient biographical tradition performs the ultimate act of heterosexualising Sappho by claiming that she leapt to her death from the cliffs of Leucas because Phaon would not reciprocate her love. Flash-forward to the late 19th century, when archaeologists were beginning to find papyrus fragments in Egypt containing new bits of Sappho: as Miriam Kamil writes in ‘I Shall — #$% You And *@$# You’ (2019), many English translators censored Sappho’s lesbianism by changing female pronouns to male.

Given this history, it is difficult to overstate the significance of Heim’s discovery of Bilitis’s poetry: here, at last, was the material evidence and textual perspective of a female contemporary to Sappho and her lovers.

The catch? ‘Bilitis’ was fake.

Bilitis’s poetry and the story of its discovery were all the invention of Pierre Louÿs, the man who purported to have translated her poems for the first time. We might be tempted to classify Louÿs’s concoction as a forgery, a text created by a person who intends to deceive an audience by passing it off as something other than what it is. However, upon closer inspection, The Songs of Bilitis is a thinly veiled literary hoax, a creation that is more of a literary game than a genuine attempt at deception.

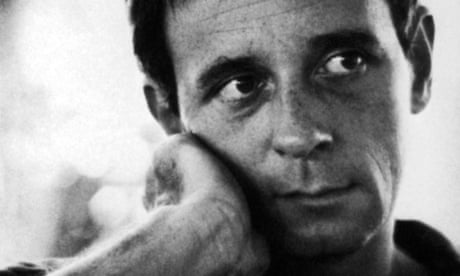

Louÿs was no stranger to the contemporary literary scene as both a translator and an imitator of (authentic) ancient texts. He also happened to be close friends with Oscar Wilde, sharing with him literary interests in art’s power to imitate and deceive, as well as erotic interests in sexual tourism in French-colonised Algeria. Only one year before releasing The Songs of Bilitis, Louÿs had published a French translation of epigrams by the 1st-century BCE poet Meleager of Gadara (now the city of Umm Qais in Jordan). It is likely that Louÿs found inspiration for fabricating Bilitis in the genre of the epigram itself. Epigrams are short poems originally written upon objects such as pots, walls or tombs – the site of Bilitis’s discovery. As a ‘lower’ literary genre, epigrams are often sexually explicit. Louÿs lifted some of Bilitis’s songs wholesale (with minor tweaks) from the erotic Book 5 of the Greek Anthology, a collection of thousands of Greek poems. Finally, by composing epigrams under the name of Bilitis, Louÿs took his cue from an ancient authorial move associated with the epigram: some epigram authors, remaining anonymous themselves, composed epigrams pseudonymously, that is, by attaching someone else’s name (often that of a dead author) to their epigram. Some of the epigrams in the Greek Anthology purport to be composed by Sappho herself, something Louÿs no doubt had in mind as he chose ‘Bilitis’ for his authorial mask.

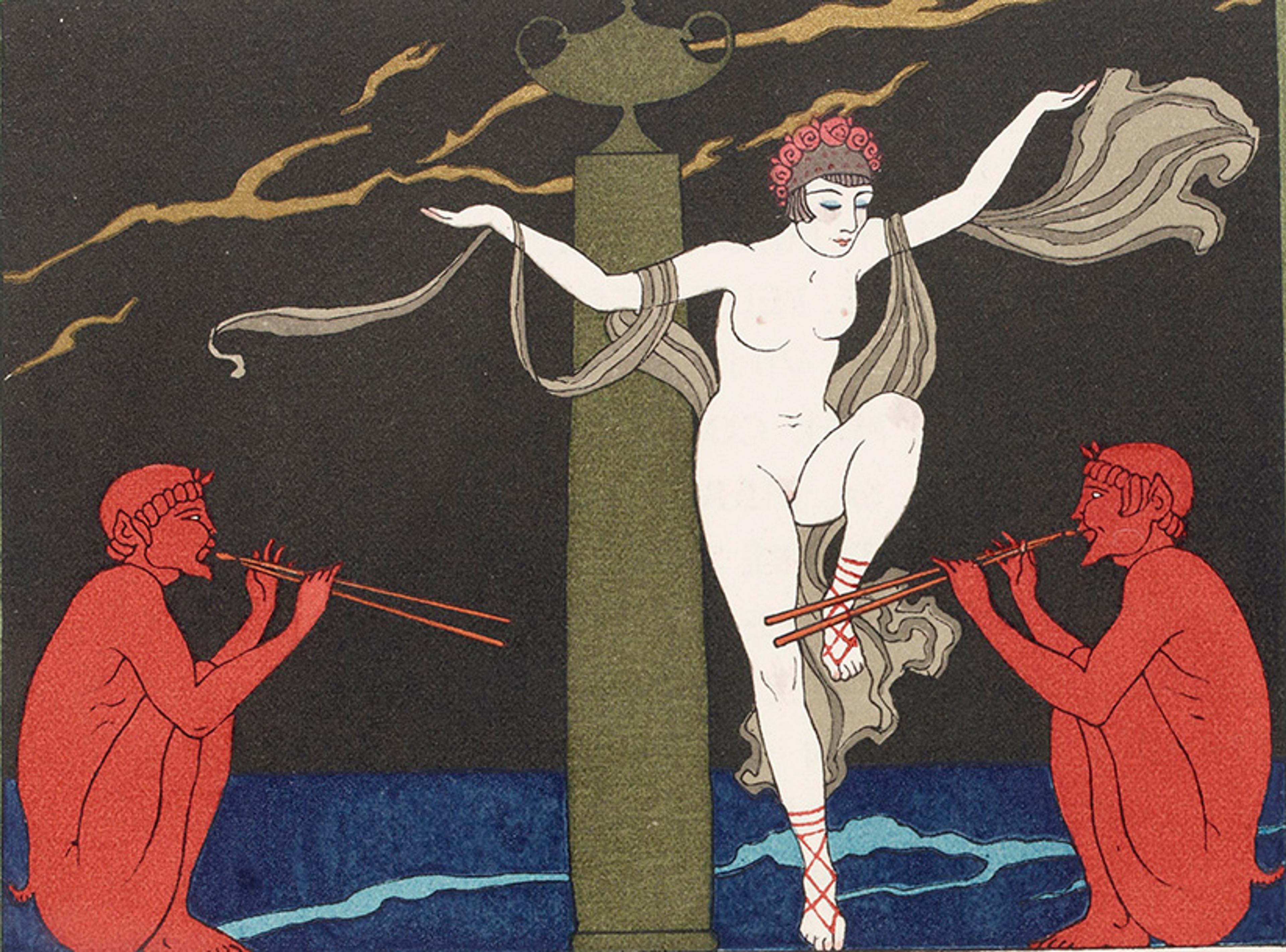

The book was published amidst intense cultural debates about the quality and nature of Sappho’s lesbian desire

Louÿs ‘plays’ the forger and wants his readers to appreciate the cleverness of his performance. One clear example of this lies in the fiction Louÿs creates around the poems’ provenance. In The Songs of Bilitis, Louÿs inserts a prefatory ‘Life of Bilitis’, in which he narrates how Herr G Heim excavated Bilitis’s tomb and brought her poetry to light. The choice of this name encodes a clever joke: when read with a German pronunciation, Herr G Heim becomes Herr Geheim, aka ‘Sir Secret’. The real origin of Bilitis’s poetry – not Herr G Heim’s pickaxe but Pierre Louÿs’s pen – is a secret lying in plain sight for clever readers to detect. We also learn from this preface that Bilitis had a Greek father and a Phoenician mother, but that she might have never known her father, given that he is nowhere mentioned in her poetry. It is tempting to see Bilitis’s dubious paternity as another place where Louÿs tips his hat as Bilitis’s literary progenitor.

Another playful way that Louÿs generates an aura of mystery around Bilitis’s poetry is the inclusion of a table of contents that labels some of the poems ‘untranslated’. Readers who are taken in by the ruse might believe that, given the sexual nature of many of the songs, some of them were too explicit to translate for a popular audience. But for readers who get the game Louÿs is playing, this performance of self-censorship puts Bilitis in the same category as actual ancient writers such as Catullus, Martial or Juvenal, whose sexual obscenities were handled in 19th-century translations by leaving them in untranslated Latin.

Even if The Songs of Bilitis was more of a literary hoax than a forgery, Louÿs nonetheless followed the forger’s playbook in targeting the desires of his contemporary audience. Not only did his ‘discovery’ hit the shelves as new papyrus fragments of Sappho’s poetry were being excavated in Egypt, but the book was also published amid intense cultural debates about the quality and nature of Sappho’s lesbian desire. For Natalie Barney and Renée Vivien – two prominent lesbian intellectuals (and close friends of Louÿs’s) – it was irrelevant that Bilitis was fake: they praised Louÿs for representing an unequivocally lesbian Sappho, and they went on to publish their own translations and imitations of Sappho’s poetry.

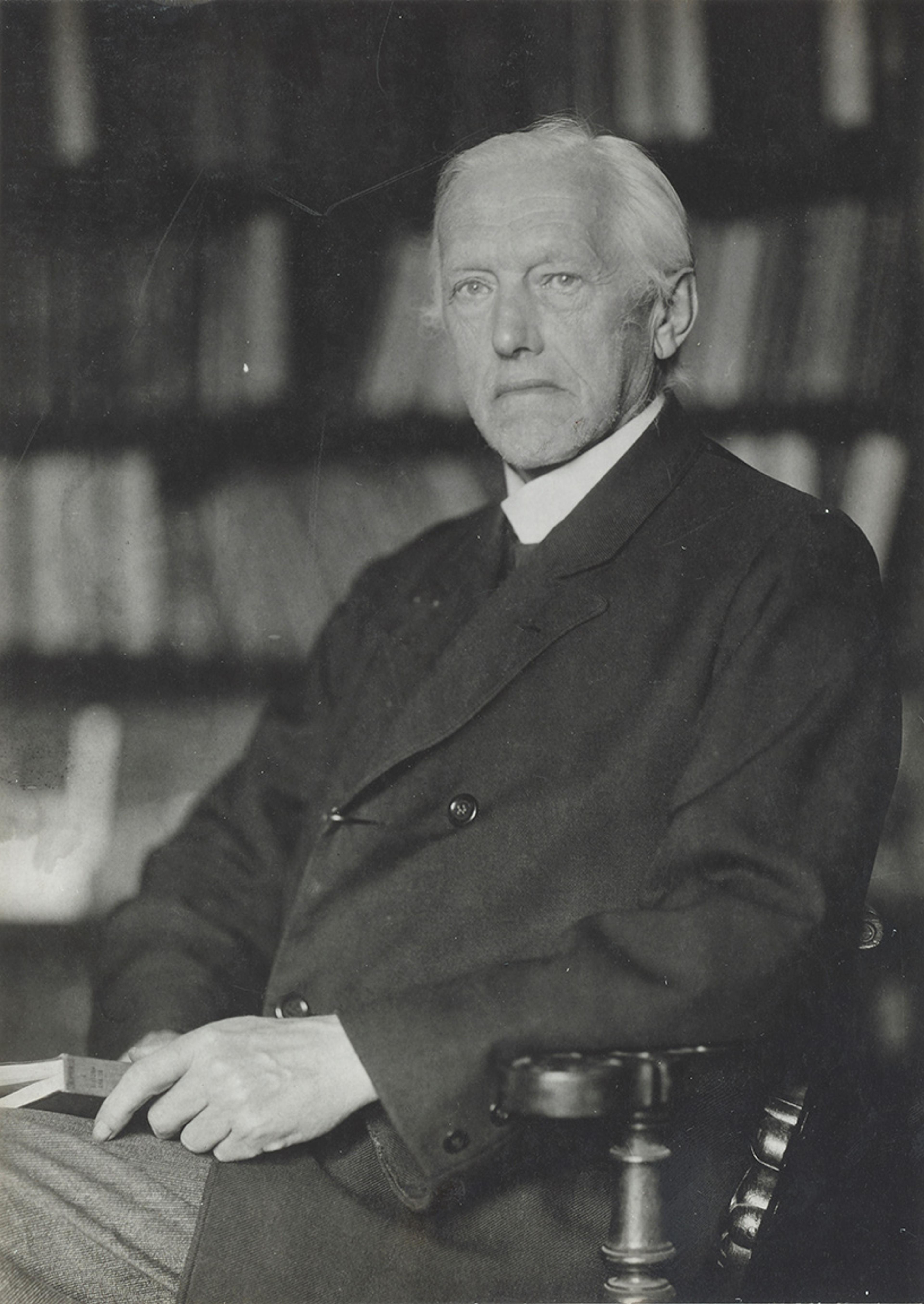

The greatest badge of honour for Louÿs’s literary creation, however, came from its most incendiary critic: the German philologist giant Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff. In 1896, Wilamowitz published a scathing 16-page review of The Songs of Bilitis. His ire did not mellow as time passed, for he reprinted this same review as the centrepiece to his monograph Sappho und Simonides (1913). The opening of the review is worth quoting in full (my translation from German):

A volume of French poetry, some of which is disgustingly lewd, may seem unsuitable for review in this place: but I find it worthy of consideration, and seize this opportunity to address matters long dear to my heart. I’m concerned with the purity of a great woman: I’m not afraid to put my hands in shit.

The ‘great woman’ Wilamowitz refers to here is not Bilitis, of course, but Sappho. Bilitis is the filth that has corrupted her ‘purity’, by which Wilamowitz means Sappho’s (hetero)sexual chastity. In this regard, Wilamowitz used his review of contemporary French poetry to rekindle an argument made about Sappho in the early 19th century by the scholar Friedrich Welcker. Welcker wrote a book called Sappho von einem herrschenden Vorurtheil befreyt (1816), or ‘Sappho: Freed from a Prevailing Prejudice’, in which he argued that Sappho was not, in the lingo of the time, a ‘tribade’, but rather a schoolteacher preparing girls for society and marriage with men. Wilamowitz follows the path paved by Welcker, claiming that it is later readers such as Louÿs who bring their own ‘unnaturalness’ (Unnatur) to Sappho’s poetry.

Wilamowitz’s fiery takedown did not succeed in quashing the hype

The motive of Wilamowitz’s review is to purify Sappho of lesbian eroticism via her association with Bilitis (whose primary female lover is not, in fact, Sappho, but rather someone called Mnasidika, whose beauty Sappho herself praises in fragment 82a: ‘Mnasidika more finely shaped than soft Gyrinno …’). Curiously, however, most of his review is spent criticising various poetic and linguistic aspects of Louÿs’s poetry. Wilamowitz plays the philological critic in unveiling the many anachronistic details littered throughout the poems, observing that they suit more the literature of the later Hellenistic and imperial period (when Greece was under Roman control) rather than the ‘true Hellenic’ (ie, classical) spirit of Sappho’s time. Wilamowitz is as upset at Louÿs’s anachronistic mixing of literary genres and language as he is by Sappho’s sexual mixing with Bilitis. For him, The Songs of Bilitis presents both a moral and textual threat to a supposedly pure Sappho. Wilamowitz’s review promulgates a misogynist, homophobic theory about Sappho, and it cloaks this mission in the seemingly objective rhetoric of classical philology.

Wilamowitz’s fiery takedown did not succeed in quashing the hype around The Songs of Bilitis. In fact, the opposite occurred. Louÿs himself cited Wilamowitz’s review in the bibliography to the expanded 1898 edition of The Songs of Bilitis. Why would Louÿs draw attention to such negative reception? Wilamowitz’s eye as a philologist laid bare for readers all the potential sources that Louÿs imitated as he composed his fake ancient poems, thus highlighting the scholarly work that went into making Bilitis. Wilamowitz takes Louÿs’s poems so seriously as imitations that he treats them as if they actually were translations of authentic ancient Greek poems. The critic’s takedown becomes the forger’s badge of pride.

Still, Louÿs’s bold citation of Wilamowitz’s homophobic review should give us pause. If Wilamowitz was concerned to carry Welcker’s torch and purify Sappho from the taint of female homoeroticism, Louÿs did not exactly free Sappho from male-centred, misogynist approaches to her poetry, a tradition that, as we’ve seen, was underway already in classical antiquity.

Although he represented a homoerotic Sappho – and received praise from contemporary lesbian readers for doing so – Louÿs in fact had drawn inspiration for the character of Bilitis from his sexual involvement with a 16-year-old Algerian girl. Louÿs invented a literary fiction that fit squarely in a 19th-century French literary tradition of male-authored, voyeuristic, orientalising portrayals of lesbian desire, a tradition grounded in the material conditions and power dynamics of European colonialism and sexual tourism. In this regard, Sappho and Bilitis were simply springboards for Louÿs to cater to a European readership hungry for images of the exoticised lesbian other.

These lesbians took the licence that they, too, could participate in the contested afterlife of Sappho

But this is not the end of Bilitis’s story. Some 60 years after the ‘discovery’ of Bilitis, a remarkable coincidence occurred, igniting a new legacy for Bilitis that Louÿs could never have predicted. In 1955, The Songs of Bilitis, previously available only through limited, expensive and privately printed editions, was republished by Avon, a press that sought to rival Pocket Books (the first mass-market paperback publisher in the United States) by making a wider range of literature – from science fiction to smut – accessible to a popular audience in the form of cheap paperbacks. That same autumn, four lesbian couples gathered in San Francisco to form a secret club. They desired a space where lesbians could socialise beyond the surveillance of their parents, families and employers, and outside of gay bars, which were frequently subject to police raids.

When it came time to make a name for their group, they had to be careful not to pick anything that could put their members at risk, given the intense homophobia of the McCarthy era. Nancy, a factory worker whose last name we don’t know, suggested ‘Daughters of Bilitis’. She was met with blank stares. Nancy explained: she had encountered a translation of Bilitis’s poetry in a volume by Pierre Louÿs. She had brought that very volume with her to the meeting. What intrigued Nancy was that this Bilitis was a contemporary of the ancient Greek poet Sappho on the island of Lesbos in the late 7th century BCE. Nancy’s partner Priscilla chimed in: ‘“Bilitis” would mean something to us, but not to any outsider. If anyone asked us, we could always say we belong to a poetry club.’ The women agreed to name themselves after this obscure figure. Thus was born the ‘Daughters of Bilitis’ (or DOB), a group that would become the first lesbian social-political organisation in the US, active until 1995.

It is easy to take a cynical view of these lesbians’ decision to name themselves after a fictive ancient lesbian. The women were cognisant of the fact that Louÿs had invented Bilitis, but that did not deter them from making something out of what was available to them – and conducive to their precarious social conditions – at the time. If these lesbians took anything from Louÿs, it was the licence that they, too, could participate in the contested afterlife of the fragmentary Sappho. Unlike Louÿs, they would author a chapter under Bilitis’s name by and for lesbians.