Ida Lewis, Newport’s Legendary Lighthouse Keeper

In the mid-1800s, Ida Lewis’s daring sea rescues became a media sensation, leading to hundreds of telegrams, gifts, and marriage proposals. All Ida wanted to do was tend to her lighthouse.

Ida Lewis in a rowboat, ca. 1900 (Newport Historical Society)

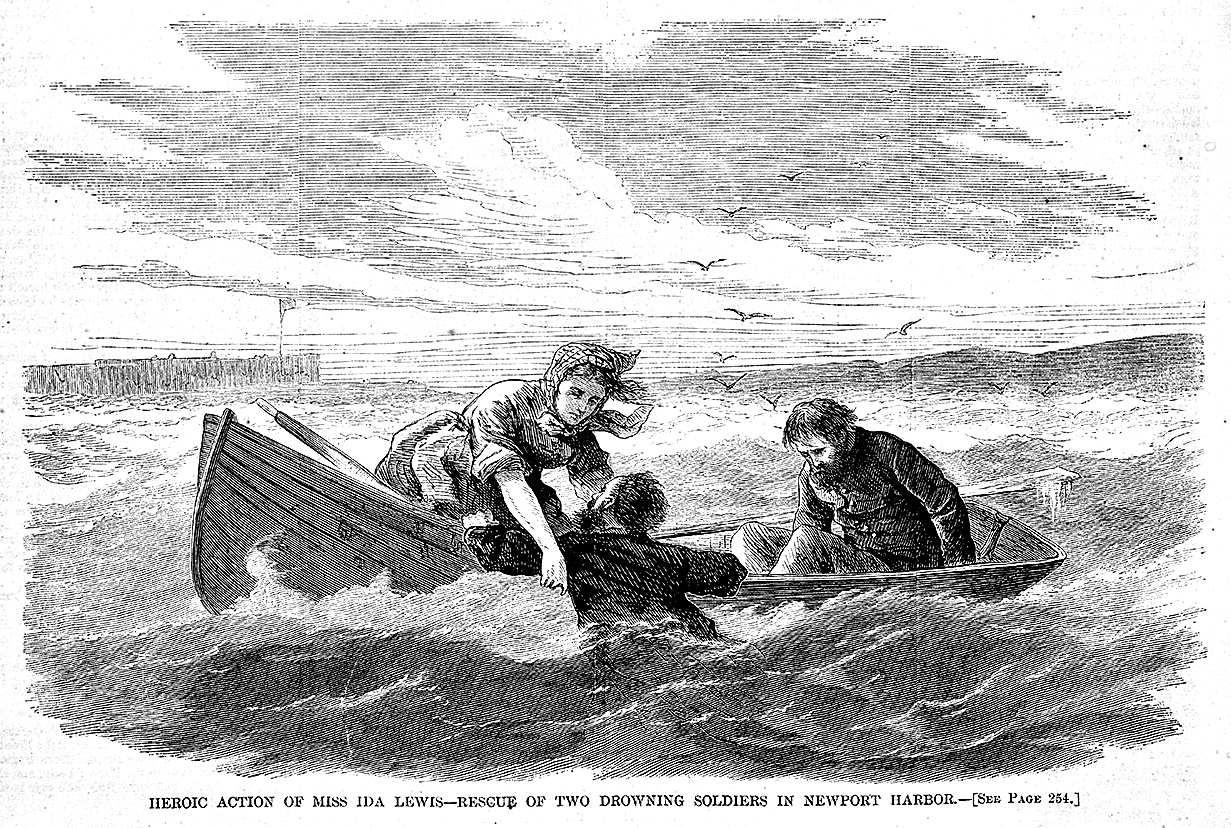

The events that led to Ida Lewis being called “The Bravest Woman in America” began on the blustery night of March 29, 1869, on Lime Rock Island, after her mother Zoradia spotted two men clinging to an overturned boat in the churning waves and screaming for help. “Ida, O my god! Ida, run quick! A boat has capsized, and men are drowning. Run quick, Ida!” she yelled to her daughter.

Ida and her younger brother Hosea immediately ran out of the house and jumped into a small skiff. Taking the icy oars, she rowed against a high wind to rescue the drowning men. Despite the freezing, wintery weather, she and Hosea lifted the choking men into the skiff, rowed them back to shore, and brought them into their home. The men were soldiers from nearby Fort Adams. As told in Lighthouse Keeper’s Daughter, Sergeant James Adams was barely able to “totter up to the house” and Private John McLoughlin was unconscious, but once revived and fed both recovered. Later, Sergent Adams told Ida’s other brother, Rudolph, “When I saw the boat approaching and a woman rowing, I thought She’s only a woman and she will never reach us. But I soon changed my mind.”

That was not the first time Ida had saved lives. By then she had already rescued three schoolboys and two other groups of men from drowning; during one rescue, Ida had saved four men whose boat had capsized in Newport Harbor. She was only twelve.

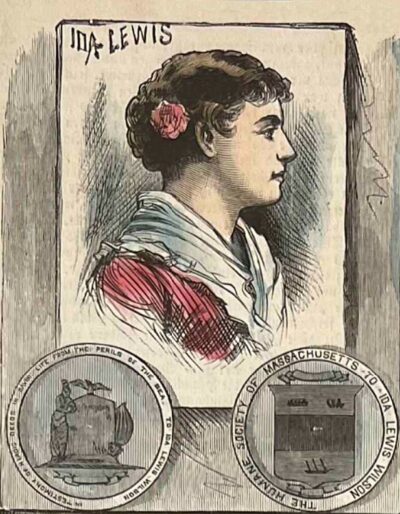

But her rescue of 1869 was so improbable that reporters flocked to Newport to interview her. On April 12, the New York Tribune carried Ida’s story, followed by articles in Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, which printed an etching of Ida’s pleasant face, strong features and wide-set hazel eyes. Adding to the story’s sensationalism was her weight of 103 pounds. Readers were riveted and soon besieged Ida with hundreds of telegrams, phone calls, gifts, and marriage proposals.

Shy and modest, Ida recoiled from the attention. When asked what motivated the rescue, she explained it as a moral obligation. “If there were some people out there who needed help, I would get into my boat and go to them even if I knew I couldn’t get back. Wouldn’t you?”

Readers were so overwhelmed by her courage that they collected funds to honor her. On July 4, 1869, in a public ceremony in Boston, they paraded a magnificent rescue boat through the streets, which was then presented to Ida. Among the audience were politicians and military leaders like Ulysses S. Grant, General Tecumseh Sherman, and Admiral George Dewey along with many wealthy Gilded Age summer residents of Newport who were then building estates along the shore. To the audience’s disappointment, she refused to address the crowd, leading prominent abolitionist Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson to explain, “Miss Lewis desires me to say that she has never made a speech in her life and…doesn’t expect to begin now.”

Later that summer, women’s rights leaders Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton visited Newport and met Ida, whom they cited as a “young heroine” and an example of women’s unsung abilities.

Born on February 25, 1842, Idawalley Zoradia Lewis was the oldest of the four children of Zoradia and Captain Hosea Lewis of the Revenue Cutter Service, the forerunner of the U.S. Coast Guard. In 1854 after the Lighthouse Service appointed Ida’s father as keeper, young Ida routinely sailed with him from Newport to Lime Rock Island to help maintain the light. Three years later when a house was built on the island and the light relocated there in a special second floor “lanthern” room, the Lewises moved to Lime Rock. Tragedy struck four months later when Ida’s father suffered a paralytic stroke, forcing her mother Zoradia to assume his keeper duties.

By then everyone in the family knew Ida was dependable, had unusual strength, and was a skilled sailor. Her brother Rudolf bragged, “Ida… can hold one to wind’ard in a gale better than any man I ever saw, wet an oar, and yes do it too when the sea is breaking over her.” Consequently, after her father’s stroke, she rowed her siblings to school and returned to the island with supplies from Newport.

Over the next 14 years, Ida helped her mother tend the light until her father died in 1877. A year later, Zoradia, who was ill with cancer, also died, leaving Ida to serve as keeper, maintain the family home, and care for a frail sister.

Being a lighthouse keeper was demanding. It was a job traditionally done by men. The beacon came from an oil-burning lantern housed in a wooden or iron frame surrounded by thick panes of glass. A solid wick suspended from the top of the frame enabled the oil (which needed to be refilled two or three times a night) to burn through the darkness. A Fresnel lens 17 inches tall and 11 ¾ inches in diameter reflected the burning oil, its light beaming far out beyond Newport Harbor. Every evening before dusk Ida trimmed the wick and adjusted the glass vents of the lens to create a proper draft. During the day, she cleaned the delicate panes of the lens, inspected and cleaned parts of the lantern, and removed carbon and other impurities. Those duties had to be performed carefully. If not, and the beacon failed, the lives of sailors at sea could be endangered.

Since Ida never kept records, no one knows how many rescues she achieved. Besides the famous 1869 rescue, several others were well known. The first occurred on a February 1866 night when she pulled three drunken soldiers from the waters after they “borrowed” her brother’s skiff and capsized it. The second happened the next January when three farmhands herded one of tycoon August Belmont’s prize sheep down Newport’s Main Street. Unexpectedly, the animal bolted and plunged into the harbor. Panicked, the trio jumped into Ida’s brother’s skiff to capture it but then overturned the boat. Again, Ida leapt into her own skiff and saved the drowning men whose hands were so numb from the frigid water that they barely grasped the sides of the capsized hull.

In 1870 Ida was officially appointed the Lighthouse Keeper of Lime Rock and awarded a salary of $750 per year (about $17,000 today). That same year she married Captain William Heard Wilson but became so unhappy that she soon left him and returned to her duties at Lime Rock Lighthouse.

Later, she rescued two more soldiers from Fort Adams who had fallen through the ice, prompting the United States government to award her the Gold Lifesaving Medal in 1881. Decades later, in 1907, Congress bestowed the first American Cross of Honor upon the aging Ida.

But awards, even national ones, meant little to her. “The light is my child and I know when it needs me, even if I sleep,” she once said. It was only when Ida died at age 69 on October 24, 1911, that her light finally went out.

Nancy Rubin Stuart often writes about women and social history. She is the author of The Muse of the Revolution: The Secret Pen of Mercy Otis Warren and the Founding of a Nation. Visit nancyrubinstuart.com.