Since I started reading here at Scottie’s, I’ve thought especially of Bayard Rustin during Black History month. I learned of him (aside from him being at the side of Rev. MLK Jr.) from The Nation magazine back in the early 1990s. Mr. Rustin finally got a movie in 2023, and I’ve wondered about other representation within. There is a veritable trove of information, so here is some of that. Enjoy with your favorite beverage. -A.

=====

Voice of the day

God does not require us to achieve any of the good tasks that humanity must pursue. What God requires of us is that we not stop trying.

– Bayard Rustin

=====

Black Queer History is American History

By Tymia Ballard, Communities of Color Junior Associate

it’s important to note the amount of BIPOC Queer History that has been an integral part of American history but has unfortunately been largely erased. Queer history surrounding people of color is deeply interwoven with American history, revealing critical insights into the nation’s progress in civil rights, social justice, and cultural evolution. To understand American history fully, it’s essential to acknowledge how Black queer individuals have shaped and influenced pivotal movements, art, and thought in the U.S. Despite facing intersectional challenges related to both race and sexual orientation, Black queer Americans have persistently fought for visibility, acceptance, and equality, contributing a legacy that has strengthened America’s commitment to inclusion and diversity.

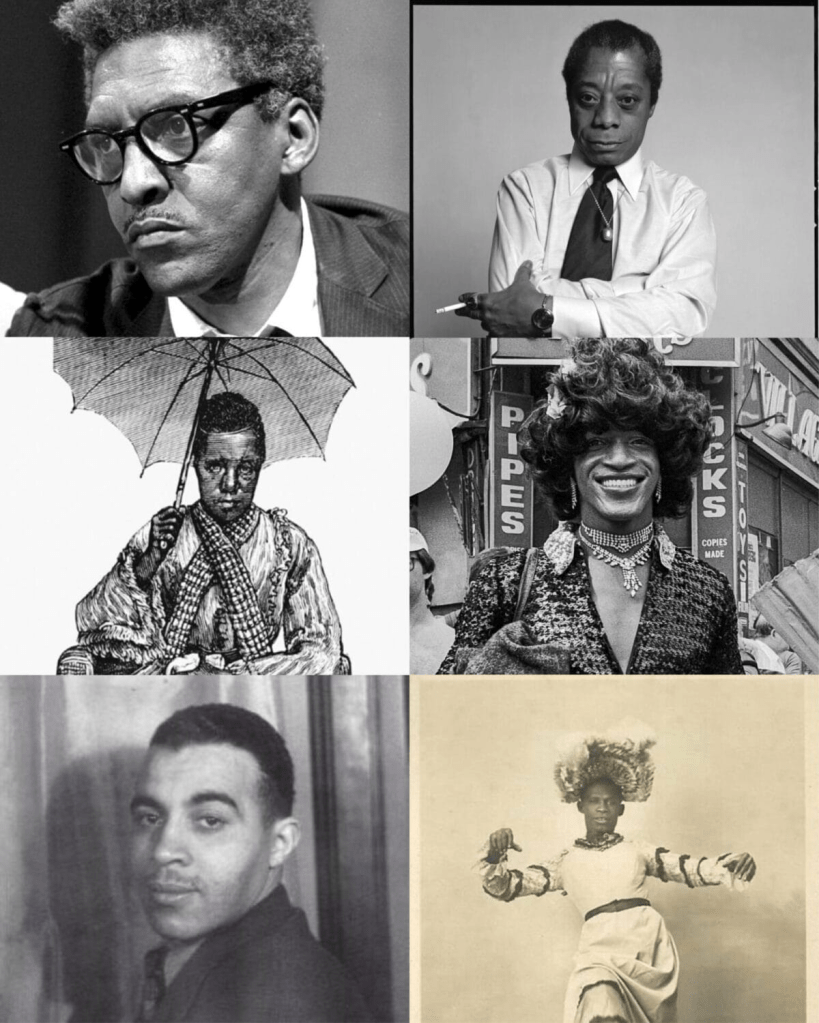

Black queer history includes significant contributions to American arts and culture. From the Harlem Renaissance to contemporary music and fashion, Black queer individuals have played central roles in defining American aesthetics and storytelling. The Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, for example, was driven by several Black queer artists, including poets like Langston Hughes and novelists like Richard Bruce Nugent, whose works celebrated Black identity while also subtly addressing queer themes. These artists expanded narratives around Black life in America, blending the experiences of race and sexuality into a singular, expressive voice.

The contributions of Black queer Americans to political activism are also inseparable from American history, especially when considering the origins of LGBTQ+ advocacy. These activists confronted police harassment and societal prejudice, laying the groundwork for the LGBTQ+ rights movement in the U.S. (snip-click through to see the stories)

https://glaad.org/black-queer-history-is-america-history/

=====

The Harlem Renaissance in Black Queer History

African American literary critic and professor Henry Louis Gates once reflected that the Harlem Renaissance was “surely as gay as it was Black, not that it was exclusively either of these.” Gates’s comments point to the often-overlooked place of the Harlem Renaissance within queer history.

The Harlem Renaissance, a literary and cultural flowering centered in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood that lasted from roughly the early 1920s through the mid-1930s, marked a turning point in African American culture. Developments from Zora Neale Hurston’s folklore-influenced fiction to Duke Ellington’s colorful orchestrations reflected an assertive and forward-thinking Black identity that philosopher Alain Locke dubbed “The New Negro.”

Black queer artists and intellectuals were among the most influential contributors to this cultural movement. Like other queer people in early twentieth century America, they were usually forced to conceal their sexualities and gender identities. Many leading figures of the period, including Countee Cullen, Bessie Smith, and Alain Locke, are believed to have pursued same-sex relationships in their private lives, even as they maintained public personas that were more acceptable to mainstream audiences. From a modern vantage point, the work of these artists and their peers is part of the foundation of modern Black LGBTQ art.

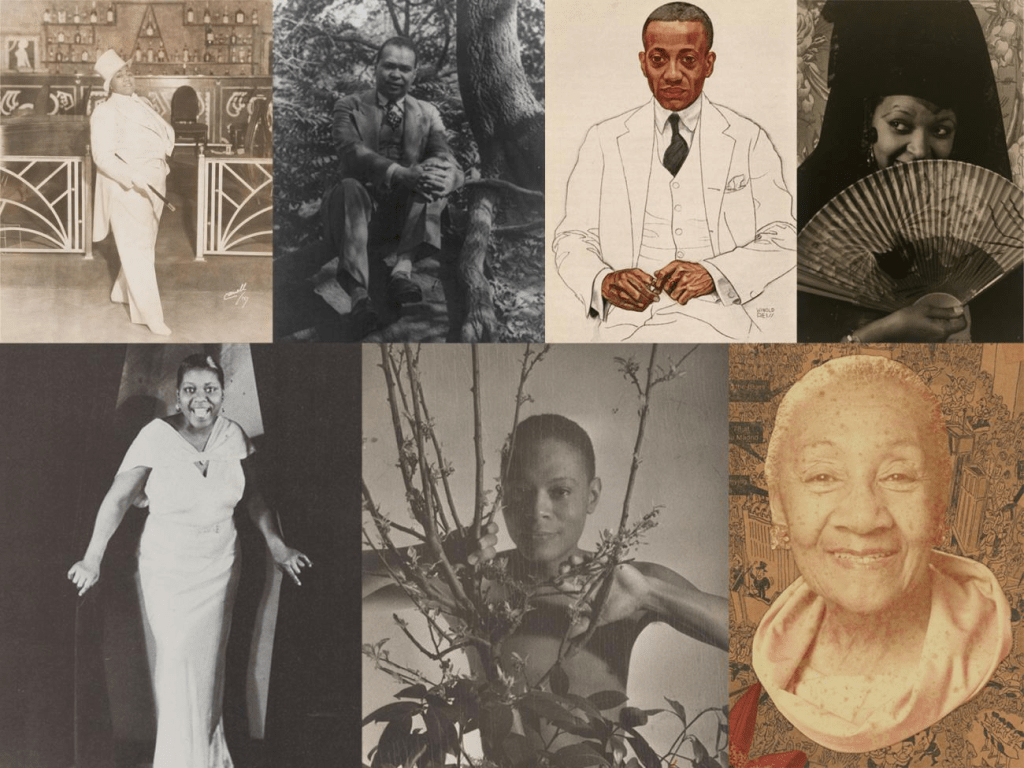

Top row l to r: Gladys Bentley, ca. 1940. 2013.46.25.82; Countee Cullen by Carl Van Vechten, 1941. Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division; Alain Locke by Winold Reiss, 1925. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Ethel Waters as Carmen by Carl Van Vechten, 1934. 2010.42.4

Bottom row l to r: Bessie Smith from Delegate magazine, 1975. Gift of Anne B. Patrick and the family of Hilda E. Stokely. 2012.167.9; Jimmie Daniels, early 1930s. Gift of Paul Bodden in memory of Thad McGar and James “Jimmie” Daniels. TA2020.19.3.1; Alberta Hunter, date unknown. Gift of Paul Bodden in memory of Thad McGar and James “Jimmie” Daniels. A2020.19.1.2

(snip-do click through to see. There is a wealth of history: writers, blueswomen, entertainers. There is even a video they cannot play due to restrictions, and then yet more historical information.)

https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/harlem-renaissance-black-queer-history

=====

Hidden figures in queer Black history

Throughout February, in honor of Black History Month, we’ve been busy on Stonewall’s Instagram highlighting some of the lesser-known figures in queer Black history. These bold individuals lead with bravery and authenticity, moved the needle on LGBTQ liberation and racial justice, and paved the way for future generations. Each one of these icons should be a household name! Read on to learn some of the hidden history of our intertwining and ongoing struggles for equality.

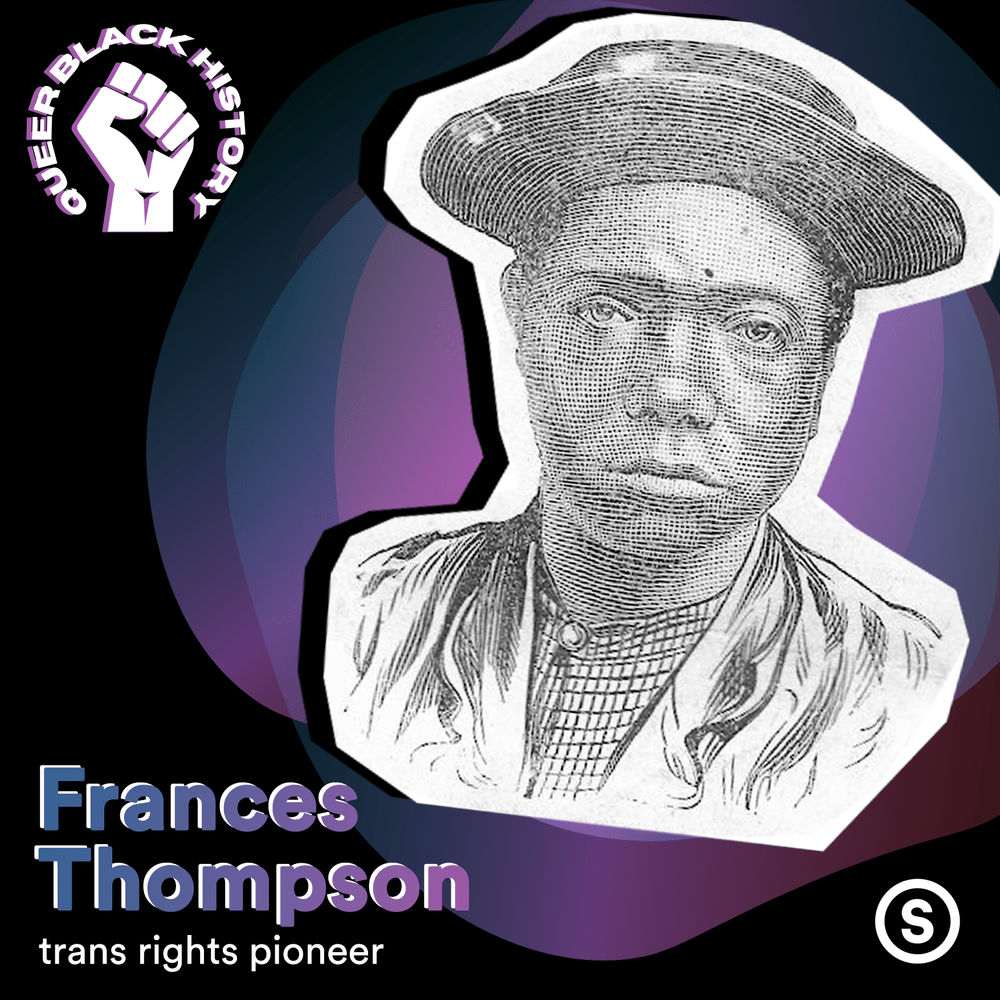

Frances Thompson – Trans Rights Pioneer

Believed to be the first transgender woman to testify before the United States Congress, Frances Thompson was born into slavery in 1840. Living as a free woman by the age of 26, Thompson was an advocate for bodily autonomy, an anti-rape activist, and she played a pivotal role in getting the US government to enact legislation protecting the civil rights of newly emancipated Black people.

Thompson’s bold legacy lives on today as we continue fighting for self-determination, dignity, and justice for queer and trans people. Her story serves as a reminder that queer and trans people have always been here, and we always will be. Always.

Learn more about Frances here.

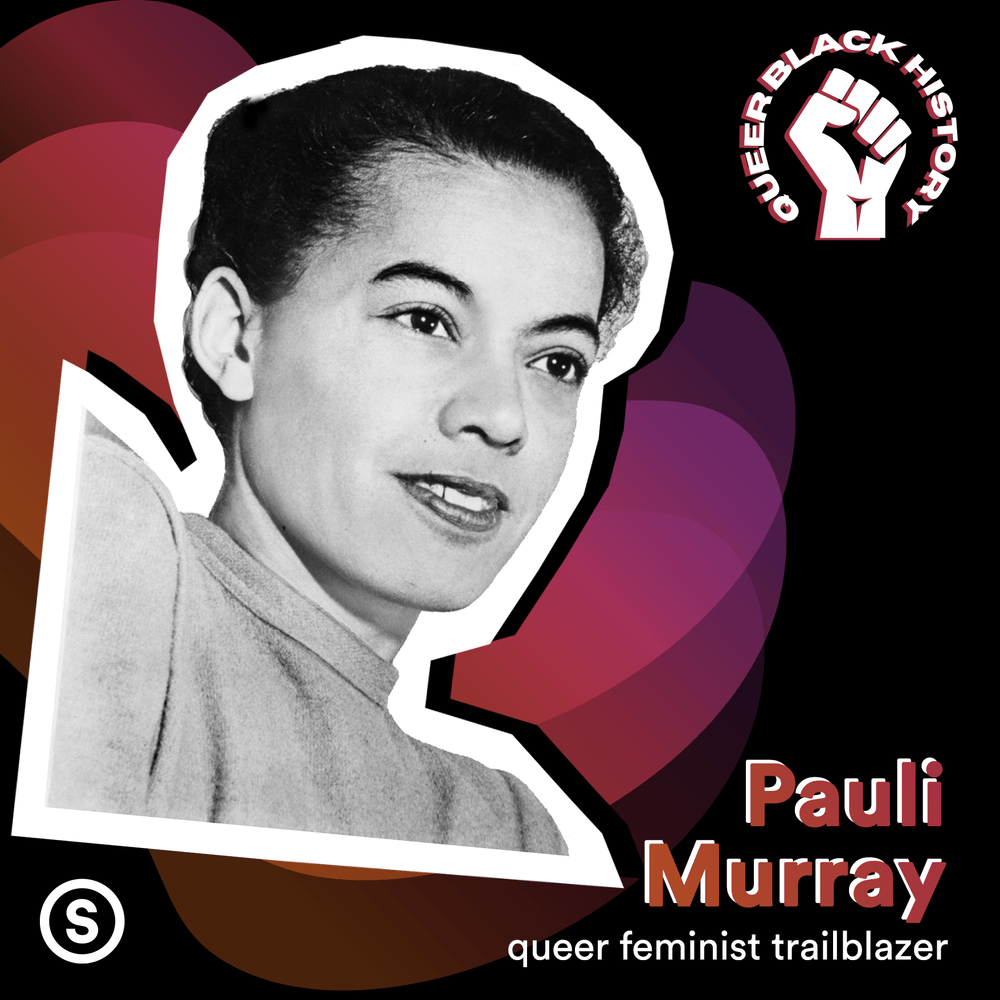

Pauli Murray – Queer Feminist Trailblazer

One of the most pivotal – yet often forgotten – figures of the Civil Rights Movement, Pauli Murray was a Black, queer, feminist lawyer who dedicated a lifetime to challenging preconceived notions of race, gender, sexuality, and religion. Murray pioneered many of the non-violent protest tactics of the Jim Crow era, and authored legal arguments that played a pivotal role in outlawing systemic racism and sexism.

Many of Murray’s contributions to the Civil Rights Movement were erased from the broader narrative as same-gender relationships and gender nonconformity disrupted the respectability expectations of the era. Many historians believe that if the language existed at the time, Murray may have identified as a trans man.

Later in life, Murray became an Episcopal priest, and was eventually canonized as a saint – a queer saint!

Norris B. Herndon – Funder for Equal Rights

After the death of his father in 1927, Norris B. Herndon assumed the role of president of Atlanta Life Insurance, turning the company into one of the most successful Black-owned business in the US. Using his wealth and influence to support the Civil Rights Movement, Herndon was a critical funder of Civil Rights efforts, and regularly gave generously to support MLK, Jr., HBCUs, the NAACP, and more. He even allowed key Civil Rights activist to use his offices for training purposes.

While he never publicly identified as gay or bi, many in his inner circle were aware of his relationships with men throughout his life.

Herndon’s legacy serves as a reminder of the important role that Black queer individuals have played in shaping American history.

Ma Rainey – Bisexual Blues Icon

Ma Rainey, also known as the “Mother of the Blues,” was a pioneering blues singer and one of the first openly bisexual performers in the early 20th century. Her music often expressed themes of sexual freedom and gender identity that challenged prevailing attitudes of her time.

Rainey’s songs such as “Prove It on Me Blues” and “Sissy Blues” were widely considered to be bold and unapologetic expressions of her bisexuality, and her performances often featured drag queens and other gender-nonconforming artists.

Rainey’s visibility and outspokenness about her sexuality, at a time when queerness was widely stigmatized, helped pave the way for later LGBTQ performers and activists. Today, she is celebrated as an icon of queer representation in music history.

Learn more about Ma Rainey here.

Marlon Riggs – Revolutionary Storyteller

Marlon Riggs was a pioneering filmmaker and activist whose work focused on issues of race, sexuality, and identity, seeking to challenge and subvert stereotypes of LGBTQ and Black people.

In the early 1990s, Riggs’ films, including “Tongues Untied” and “Color Adjustment,” explored the experiences of Black gay men and the intersectionality of race and sexuality. His work helped to broaden mainstream awareness and understanding of LGBTQ and Black lives, and his films were highly influential in advancing Black and queer representation in media. Riggs also worked with organizations like the National LGBTQ Task Force and ACT UP to fight for the rights of LGBTQ people and folks living with HIV/AIDS.

Riggs’ legacy continues to inspire and inform the ongoing struggle for LGBTQ liberation and racial justice.

https://www.stonewallfoundation.org/impact-winter-2023/queer-black-icons

=====

Against the Erasure of Black Queer History

Feb. 13, 2024 BY: Trevor News

American history of resistance is a history of Black LGBTQ+ people. Advancements in civil rights and greater visibility of the LGBTQ+ community overall can be attributed to the efforts of Black LGBTQ+ folks; so much of what is popular and beloved in music, fashion, culture, and even language is because of the innovations and traditions of the Black queer diaspora. All of this is born out of the need to survive oppressive and violent conditions, distinguish themselves from their white LGBTQ+ counterparts who often enjoyed greater privilege.

When there are efforts to censor Black queer history in classrooms, to prevent trans folks from changing their gender markers or using the bathrooms they prefer, we must resist. Resistance of erasure is resistance to oppression.

This Black History Month, take a moment to learn about and honor the Black LGBTQ+ movements and people who have resisted throughout history.

The Cakewalk

What we know as the art of drag and ballroom today is born out of Black queer resistance to enslavement. The cakewalk, a dance performed by enslaved people, was meant to secretly mock plantation owners who frequently galavanted and gloated their expensive clothes. Their enslavers awarded the dancers cakes, unaware they were being blankly parodied. Later during the abolition period, “cakewalks” organized by the formerly enslaved served as a celebration of freedom and continued mockery of the enslavers, featuring attendees in extravagant costumes.

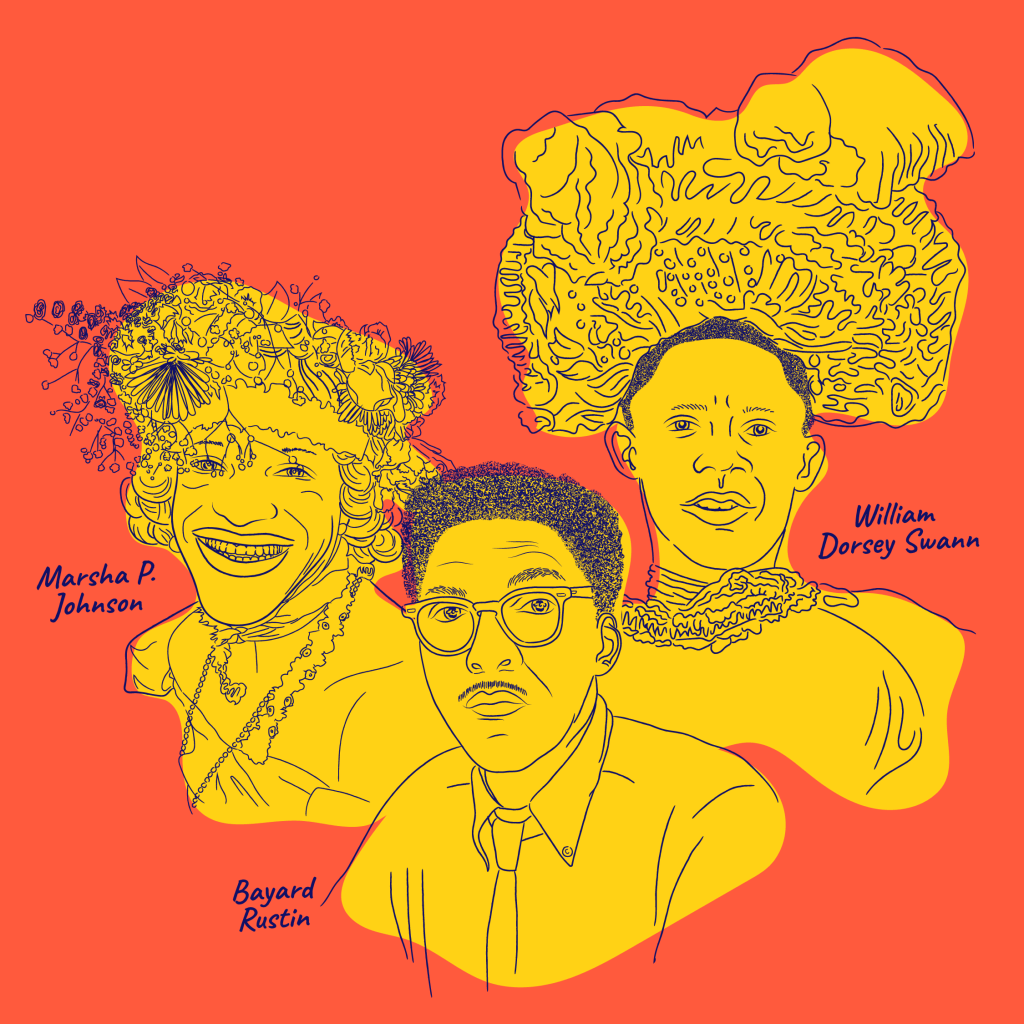

There is one particular person we can thank for the art of drag, and that is William Dorsey Swann, known now as the first drag queen. Swann, who was born into enslavement and survived to emancipation, was inspired by the “queens” of Washington D.C.’s Emancipation Day parades. He developed a form of dance for “glad rags,” also known as masquerade balls, and hosted cross-dressing balls for the community, many of which were raided by police.

This combination of dance performance and visual expression as a form of resistance survives in modern-day ballroom culture, famously depicted in the documentary film “Paris Is Burning.” Categories like “Executive Realness” serve as an opportunity for young Black queer folks — often denied positions of prominence in white society — to both mock the practices of the privileged and pretend to enjoy those privileges.

In the film, artist Dorian Corey notes: “Black people have a hard time getting anywhere. And those that do are usually straight. In a ballroom, you can be anything you want. You’re not really an executive, but you’re looking like an executive. And therefore you’re showing the straight world that ‘I can be an executive. If I had the opportunity, I could be one because I can look like one.’”

Bayard Rustin and the Civil Rights Movement

Many of us know about the work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., but not as many know about Bayard Rustin, an “angelic troublemaker,” his mentor and collaborator during the civil rights movement of the 50s and 60s. Rustin was in fact the primary organizer of the historic March on Washington in 1936, perhaps the most famous civil rights protest of all time. Rustin was also openly gay, and spent much of his life dealing with political and legal persecution because of it (recently depicted in the 2023 film “Rustin”).

(snip-do go and read the rest; it’s not too long)