‘Like walking through time’: as glaciers retreat, new worlds are being created in their wake

As Swiss glaciers melt at an ever-faster rate, new species move in and flourish, but entire ecosystems and an alpine culture can be lost

Photographs by Nicholas JR White By Katherine Hill

From the slopes behind the village of Ernen, it is possible to see the gouge where the Fiesch glacier once tumbled towards the valley in the Bernese Alps. The curved finger of ice, rumpled like tissue, cuts between high buttresses of granite and gneiss. Now it has melted out of sight.

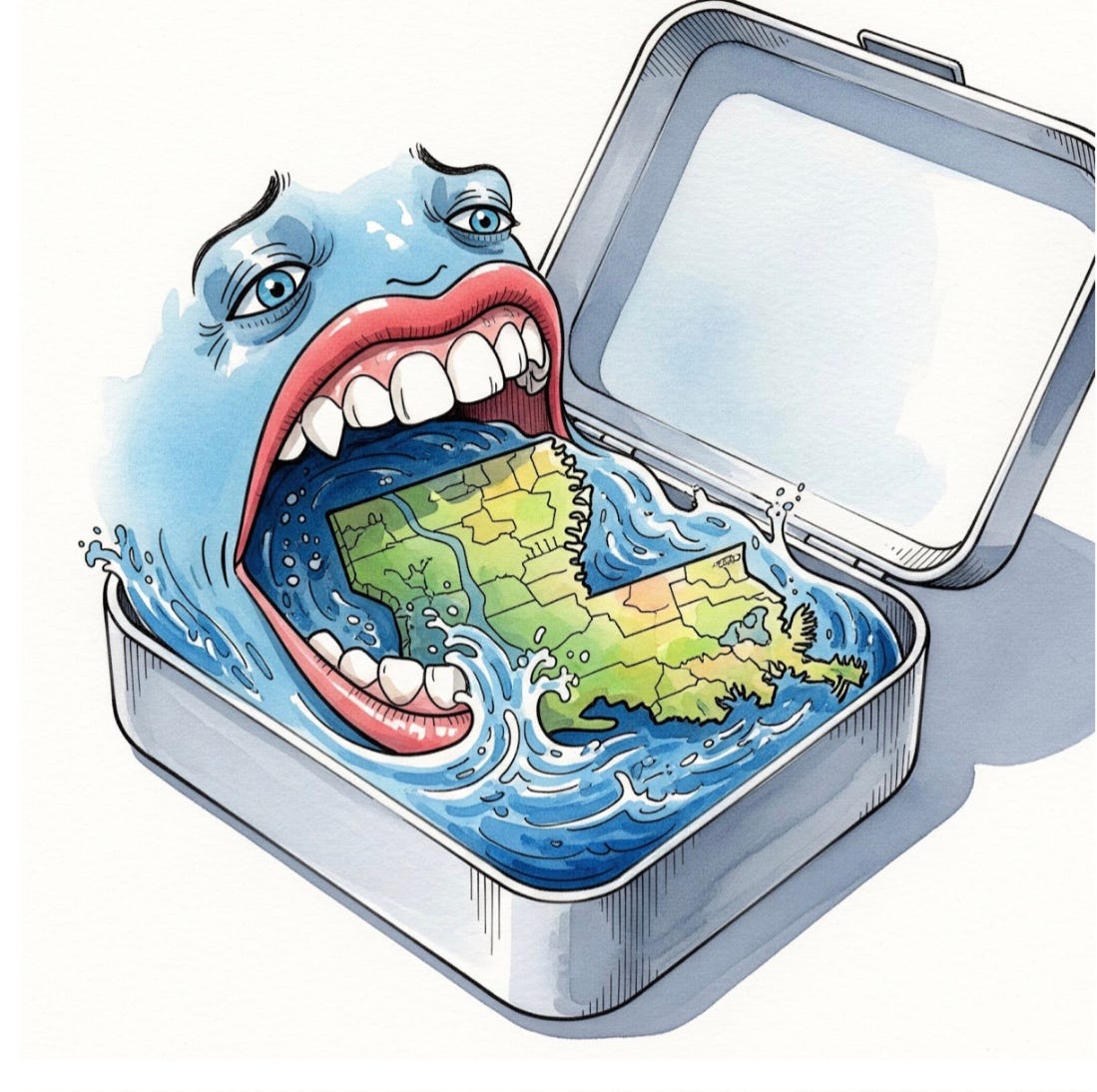

People here once feared the monstrous ice streams, describing them as devils, but now they dread their disappearance. Like other glaciers in the Alps and globally, the Fiesch is melting at ever-increasing rates. More than ice is lost when the giants disappear: cultures, societies and entire ecosystems are braided around the glaciers.

The neighbouring Great Aletsch, like the Fiesch, flows from the high plateau between the peaks of the Jungfrau-Aletsch, a Unesco region in the Swiss canton of Valais and Europe’s longest glacier. It is receding at a rate of more than 50 metres a year, but from the cable car above it remains a mighty sight.

Clouds scud across the sky and shafts of light marble the ice. On the rocky slopes leading down to the glacier from the ridge, there are pools of aquamarine brilliance, the ground speckled with startling alpine flowers. The ice feels alive, with waterfalls plunging into deep crevasses and rocks shimmering in the sun.

“It’s just so diverse, these harsh mountains and ice, and up the ridge, a totally different habitat,” says Maurus Bamert, director of the environmental education centre Pro Natura Aletsch. “This is really special.”

Participants now pray for the glacier not to vanish, but they once prayed for it to retreat and stop swallowing their meadows

Many of the living worlds in the ice and snow are not visible to the human eye. “You don’t expect a living organism on the ice,” Bamert says. But there is a rich ice-loving biotic community and surprising biodiversity that thrives in this frozen landscape.

Springtails or “glacier fleas” survive on the snow’s crust – this year alone, five new species were identified in the European Alps. But there are also algae, bacteria, fungi and ice worms, as well as spiders and beetles, which feed on springtails.

As ice melts, this landscape and its inhabitants, human and non-human, are all affected. Along the glacier’s path, ice turns to water and the rushing sound of the river becomes audible. In 1859, at the greatest extent of its thickness, the glacier reached 200 metres higher than it does now.

The landscape revealed by the melt is mostly bare rock, riven with fissures that spill across the hillside. Jasmine Noti from Aletsch Arena, the regional tourism organisation, says these widen each year, new cracks appear and routes are redesigned. The ice acts like a massive buttress, gluing the hillside together, and as it melts, slippage and instability increase.

As the edges of the glacial valley descend into the cool cover of the Aletschwald forest, “it’s like walking through time”, says Bamert. On the higher slopes, older pines dominate, but lower down the trees thin, and the pioneer species of larch and birch cover the hillside: early signs of newer postglacial reforestation.

It only takes about five to 10 years for plants to colonise the land. Further down yellow saxifrage and mountain sorrel cling to the rocks. All this was once under ice sheets, but the succession of growth tells a story of glacial retreat, historic and recent.

Tom Battin, professor of environmental sciences at Lausanne’s Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, says glacial margins are a transitional landscape where ecosystems are vanishing and appearing. An expert on the microbiology of stream ecosystems, Battin led a multiyear project on vanishing glaciers and what is lost with them.

As he walks down to the Märjelensee, one of the Aletsch’s glacial lakes, this transition is readily apparent. In this mountain hollow, there was once an expansive lake with ice cliffs around its rim. Today, the pools of water are lit by patchy sun and rain, fish jumping and bog cotton dancing in summer light.

Battin points to aquatic mosses. These, he says, could never live in glacial streams which are fast flowing and extreme. Wading into the water, he searches for the golden-brown blooms of a particular alga, Hydrurus foetidus, which is a keystone species that thrives in glacier-fed rivers, fixing carbon dioxide into organic matter.

Lee Brown, professor of aquatic sciences at Leeds University, has studied invertebrate communities in glacier-fed rivers around the world, and says we do not yet know the full importance of those that are likely to disappear.

“It’s a challenge to communicate,” he says, pointing out the crucial roles that tiny organisms have in the “trophic networks” – the nutrients flowing between organisms within an ecosystem – that connect ice, rivers, land and oceans. Biofilms, or communities of micro-organisms that stick to the surface of ice and rivers, filter the water. Glaciers wash down vital nutrients from the mountain, but their rivers may run dry when the ice melts.

Without this biodiversity which you can’t see, all that other biodiversity that people care about might disappear

Tom Battin

There are whole worlds in and around the ice, poorly known and understood until recently. Mountains are like high islands, Battin says, with unique ecosystems and endemic species.

“Without this biodiversity which you can’t see,” he says, “all that other biodiversity that people care about might disappear.”

Francesco Ficetola is a professor of environmental science at Milan University who leads the PrioritIce project examining emerging ecosystems in glacial forelands, or land exposed by the retreating ice. As it melts, he says, “there’s a powerful combined effort of organisms” to create new and increasingly complex habitats.

As something is gained, however, much is lost. Cold-climate specialists such as ptarmigan and Alpine ibex are retreating up mountains, their habitats becoming ever smaller. The Swiss pines, on whose seeds nutcracker birds feed, are also moving upwards. Specialist alpine flowers and other pioneer plants at glacier edges are threatened, pushed out by the succession of forests and meadows.

For the people of this region, too, life alongside the glacier is changing. The guides Martin Nellen and his son, Dominik, have lived with the Aletsch glacier all their life. Martin jokes that the older he gets, the farther he must climb from the ridge to the glacial valley as the ice melts. “It’s rubbish,” he says.

Martin was instrumental in raising funds for information boards, which he also helped design, that explain the life story of the Aletsch. Dominik says they feel “sad, of course” about the glacier’s retreat, but they are also proud to educate people about glaciers and the distinctive landscape of snow-covered peaks and lush pastures.

Every year at 6am on 31 July people gather for a procession that winds from the church in Fiesch to the Mariahilf chapel in the forest above. Participants now pray for the glacier not to vanish, but they once prayed for it to retreat and stop swallowing their meadows and grazing land.

Divine assistance was first requested in 1652. Rosa, one of those gathered for the pilgrimage, remembers the deep snow and cold of past years. “I have been going since I was five,” she says. “There used to be more people.”

This procession is special for the reversal of its request, but similar stories exist across the Alps. They are a reminder that something intangible is lost as glaciers disappear. The great rivers of ice have shaped the imaginations of inhabitants and visitors. Not everyone sees the glacier through the lens of faith, but many visitors – whether praying, guiding or educating – worry what the future holds.

At a place called Baseflie, a cross still stands, erected in 1818 to banish the Aletsch glacier when it threatened pastures. Today, the wooden silhouette against a blue sky seems like a memorial to all that may be lost as glaciers vanish.

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow the biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield in the Guardian app for more nature coverage