Abby Martin joins the program to discuss her new film, Earth’s Greatest Enemy which exposes the U.S. military as the world’s largest polluter. Live-streamed on November 6, 2025.

As Swiss glaciers melt at an ever-faster rate, new species move in and flourish, but entire ecosystems and an alpine culture can be lost

Photographs by Nicholas JR White By Katherine Hill

From the slopes behind the village of Ernen, it is possible to see the gouge where the Fiesch glacier once tumbled towards the valley in the Bernese Alps. The curved finger of ice, rumpled like tissue, cuts between high buttresses of granite and gneiss. Now it has melted out of sight.

People here once feared the monstrous ice streams, describing them as devils, but now they dread their disappearance. Like other glaciers in the Alps and globally, the Fiesch is melting at ever-increasing rates. More than ice is lost when the giants disappear: cultures, societies and entire ecosystems are braided around the glaciers.

The neighbouring Great Aletsch, like the Fiesch, flows from the high plateau between the peaks of the Jungfrau-Aletsch, a Unesco region in the Swiss canton of Valais and Europe’s longest glacier. It is receding at a rate of more than 50 metres a year, but from the cable car above it remains a mighty sight.

Clouds scud across the sky and shafts of light marble the ice. On the rocky slopes leading down to the glacier from the ridge, there are pools of aquamarine brilliance, the ground speckled with startling alpine flowers. The ice feels alive, with waterfalls plunging into deep crevasses and rocks shimmering in the sun.

“It’s just so diverse, these harsh mountains and ice, and up the ridge, a totally different habitat,” says Maurus Bamert, director of the environmental education centre Pro Natura Aletsch. “This is really special.”

Participants now pray for the glacier not to vanish, but they once prayed for it to retreat and stop swallowing their meadows

Many of the living worlds in the ice and snow are not visible to the human eye. “You don’t expect a living organism on the ice,” Bamert says. But there is a rich ice-loving biotic community and surprising biodiversity that thrives in this frozen landscape.

Springtails or “glacier fleas” survive on the snow’s crust – this year alone, five new species were identified in the European Alps. But there are also algae, bacteria, fungi and ice worms, as well as spiders and beetles, which feed on springtails.

As ice melts, this landscape and its inhabitants, human and non-human, are all affected. Along the glacier’s path, ice turns to water and the rushing sound of the river becomes audible. In 1859, at the greatest extent of its thickness, the glacier reached 200 metres higher than it does now.

The landscape revealed by the melt is mostly bare rock, riven with fissures that spill across the hillside. Jasmine Noti from Aletsch Arena, the regional tourism organisation, says these widen each year, new cracks appear and routes are redesigned. The ice acts like a massive buttress, gluing the hillside together, and as it melts, slippage and instability increase.

As the edges of the glacial valley descend into the cool cover of the Aletschwald forest, “it’s like walking through time”, says Bamert. On the higher slopes, older pines dominate, but lower down the trees thin, and the pioneer species of larch and birch cover the hillside: early signs of newer postglacial reforestation.

It only takes about five to 10 years for plants to colonise the land. Further down yellow saxifrage and mountain sorrel cling to the rocks. All this was once under ice sheets, but the succession of growth tells a story of glacial retreat, historic and recent.

Tom Battin, professor of environmental sciences at Lausanne’s Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, says glacial margins are a transitional landscape where ecosystems are vanishing and appearing. An expert on the microbiology of stream ecosystems, Battin led a multiyear project on vanishing glaciers and what is lost with them.

As he walks down to the Märjelensee, one of the Aletsch’s glacial lakes, this transition is readily apparent. In this mountain hollow, there was once an expansive lake with ice cliffs around its rim. Today, the pools of water are lit by patchy sun and rain, fish jumping and bog cotton dancing in summer light.

Battin points to aquatic mosses. These, he says, could never live in glacial streams which are fast flowing and extreme. Wading into the water, he searches for the golden-brown blooms of a particular alga, Hydrurus foetidus, which is a keystone species that thrives in glacier-fed rivers, fixing carbon dioxide into organic matter.

Lee Brown, professor of aquatic sciences at Leeds University, has studied invertebrate communities in glacier-fed rivers around the world, and says we do not yet know the full importance of those that are likely to disappear.

“It’s a challenge to communicate,” he says, pointing out the crucial roles that tiny organisms have in the “trophic networks” – the nutrients flowing between organisms within an ecosystem – that connect ice, rivers, land and oceans. Biofilms, or communities of micro-organisms that stick to the surface of ice and rivers, filter the water. Glaciers wash down vital nutrients from the mountain, but their rivers may run dry when the ice melts.

Without this biodiversity which you can’t see, all that other biodiversity that people care about might disappear

Tom Battin

There are whole worlds in and around the ice, poorly known and understood until recently. Mountains are like high islands, Battin says, with unique ecosystems and endemic species.

“Without this biodiversity which you can’t see,” he says, “all that other biodiversity that people care about might disappear.”

Francesco Ficetola is a professor of environmental science at Milan University who leads the PrioritIce project examining emerging ecosystems in glacial forelands, or land exposed by the retreating ice. As it melts, he says, “there’s a powerful combined effort of organisms” to create new and increasingly complex habitats.

As something is gained, however, much is lost. Cold-climate specialists such as ptarmigan and Alpine ibex are retreating up mountains, their habitats becoming ever smaller. The Swiss pines, on whose seeds nutcracker birds feed, are also moving upwards. Specialist alpine flowers and other pioneer plants at glacier edges are threatened, pushed out by the succession of forests and meadows.

For the people of this region, too, life alongside the glacier is changing. The guides Martin Nellen and his son, Dominik, have lived with the Aletsch glacier all their life. Martin jokes that the older he gets, the farther he must climb from the ridge to the glacial valley as the ice melts. “It’s rubbish,” he says.

Martin was instrumental in raising funds for information boards, which he also helped design, that explain the life story of the Aletsch. Dominik says they feel “sad, of course” about the glacier’s retreat, but they are also proud to educate people about glaciers and the distinctive landscape of snow-covered peaks and lush pastures.

Every year at 6am on 31 July people gather for a procession that winds from the church in Fiesch to the Mariahilf chapel in the forest above. Participants now pray for the glacier not to vanish, but they once prayed for it to retreat and stop swallowing their meadows and grazing land.

Divine assistance was first requested in 1652. Rosa, one of those gathered for the pilgrimage, remembers the deep snow and cold of past years. “I have been going since I was five,” she says. “There used to be more people.”

This procession is special for the reversal of its request, but similar stories exist across the Alps. They are a reminder that something intangible is lost as glaciers disappear. The great rivers of ice have shaped the imaginations of inhabitants and visitors. Not everyone sees the glacier through the lens of faith, but many visitors – whether praying, guiding or educating – worry what the future holds.

At a place called Baseflie, a cross still stands, erected in 1818 to banish the Aletsch glacier when it threatened pastures. Today, the wooden silhouette against a blue sky seems like a memorial to all that may be lost as glaciers vanish.

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow the biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield in the Guardian app for more nature coverage

This one’s about trouble for all coastal states, coming from Louisianans.

Louisiana Fights Against Becoming Another Not There No More Statistic by Jerileewei

Terrebonne Parish: Where the Rivers Meets the Sea Read on Substack

CCJC Audio Podcast Episode 00086, Season 2

“It’s not just the land we’re losing. It’s the stories. The way we talk. The smell of the air before a big storm.” — Emile Navarre

Back from his month long vacation in Chacahoula, Louisiana, Cajun Chronicle Podcast, Writer/Editor, Emile Navarre arrived for our first staff meeting armed with fresh material for a future episode, as soon as Marie Lirette, our Outreach Coordinator can reach out to potential experts on the topic of “Ain’t There No More” – a nation wide trending group talk everywhere these days, as our world changes in ways none of us could have imagined.

Here is his recount of his lifelong story telling to his family’s youngest children:

“Come closer, chérs,” he said, his voice a low rumble like the last Lafitte skiff shrimping boat of the day heading down the Bayou Lafourche over Galliano or Golden Meadow way. His cane bottom rocking chair seat creaked a steady rhythm against the worn Cedar floorboards as he said that.

The sun, a too warm blanket he could feel, but not see, was sinking somewhere behind the great oak in the yard he will always remember. He ran a hand over the cane of his chair, then rested it on the knee of a boy sitting on the steps below him. He lifted his walking stick and pointed off to the right side. “You see that big fence, hein?

“Or that levee your mamans and pépère have to climb to get home from work at the Bollinger Shipyard, just to get up to the house? We didn’t have such a thing when I was a boy. Back then, my feet knew every dip and bump in this land”.

“From our porch right down that oyster shell road to the bayou where the shrimp jumped so high, you’d swear you could catch them in your mouth, if you were quick.” A ripple of giggles ran through the children.

“Ah, oui,” he chuckled, “I lost a good tooth catching shrimp that way. But the land, it was different. We were like a river family. She’d bring us a big muddy hug every spring, and we’d be happy for it.”

“The floods, they were always a part of life. We’d move our things up high, sing songs, and wait for the water to go down. When it did, Mother Nature would leave behind a gift, a rich, dark mud that made our gardens burst with life. You could feel it in your toes, a soft, giving sponge of sandy soil that told you everything was going to be alright.”

He paused, and the laughter faded, replaced by the chirping of crickets.

“My pépère, he’d sit right here on the back porch with a fishing line tied to his toe, but in his mind, Gaia was always busy with the water. He’d talk about how the Lafourche river was a living thing, always moving, always changing. ‘She builds, and she takes away,‘ he’d say.”

“We knew that. A little bit here, a little bit there. It was a fair trade. But then came the men with the big ideas. They came from places where the land didn’t move so much. They told us we could stop the river’s big hugs. They said we could make a straight line and build high walls, so the water would stay in its place.”

Emile’s voice dropped to a conspiratorial whisper. “The young people, they thought it was wonderful. No more floods! No more moving furniture to the attic! But my pépère, he just shook his head. ‘You can’t trap a wild woman, not for long,’ he said. ‘She will find her way, and she will be angry for it.'”

“And she was,” he said, his hand now clutching his walking stick. “For years, the river was quiet, but our land, she was not. I can’t see it anymore with my eyes, but I felt it with my feet. The soil grew tired, no longer receiving her yearly gift.”

“The ground began to sag, and the bad marsh saltwater, it came closer in to say hello, not from a storm, but like a thief in the night, creeping up through the channels les Américains dug for the oil. They were for the big machines, the big money, but they were also a wound. A wound in the land that never healed.”

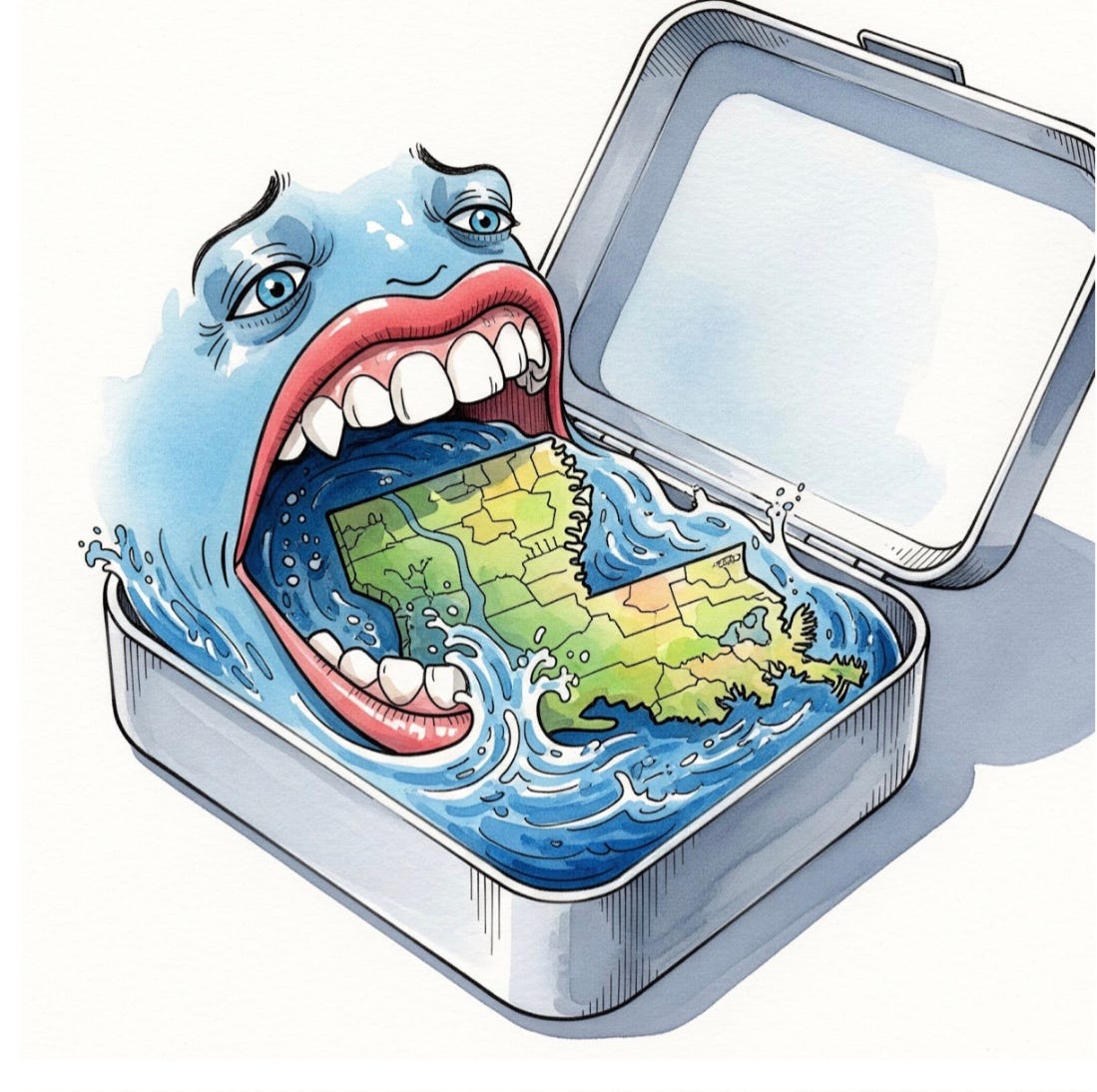

He turned his head toward the silent children, his milky blind blue eyes fixed on something only he could see. “Now, this levee you have, it protects you from the river, oui? But it holds the land in a box. It cannot breathe. The land is sick, and the ocean is hungry, taking a football field from our home every hour, the experts say.”

“I hear it in the wind now, not just the storms, but also in the sad whispers of the marsh, of the birds that have no place to land anymore. The land is leaving us, and we are left behind. We traded our river’s muddy hugs for a straight line and some high walls, and now we pay for it. Now, it’s not just the water that takes. It’s the land that gives itself away.”

The porch was silent, a stillness that was heavier than the humid air. The children looked at each other, not understanding all the words, but feeling the weight of them. One of the little girls, her braids tied with pink ribbons, quietly moved her hand to rest on the Emile’s knee as she headed inside for bed.

Emile smiled, his face creasing with a thousand invisible memories. Talking to the breeze, he raised his fist and threatened, “But you know what else my pépère said? He said, ‘As long as we tell the stories, the land is not truly gone.’ So listen, chérs, listen closely to my bedtime stories. Because now, it is your turn to remember.”

He had felt the last of the children’s light footsteps fade into the dusk, and the porch was still again except for his rocking chair. His head turned to the quiet rustling of the adults lingering on the porch. “You hear my stories, oui?” he said, his voice now lower, rougher.

“You too remember what I said about the river’s gift of mud? We didn’t know it, but we were like a family that had a big, generous table. Rivers brought food, and our land ate it. Every year, she’d get fat and happy. We thought we were so smart, so clever, when we built those high walls.”

“We told Gaia to stop eating for a while, believing for a while that she didn’t need the mud. ‘Don’t worry,’ we said, ‘We’ll protect you from the floods.’ But what we really did was put the food in a box and send it out to sea. Now, the land is starving. You cannot see it in a day, or a year. But that’s happening rapidly.”

“But I feel it in every part of my mind and body. Every year, she gets thinner, weaker. And like a sick old person who can’t stand anymore, Mother Earth’s starting to melt away. The medicine to save her is that very food we cut her off from. But the walls of levees and the canals the Corps of Engineers built? They are so high.”

“How will we get the food back to Louisiana’s coast before she’s gone entirely? That is the story my heart tells me now. And that is the story for you all to worry about. Time’s running out. I’m 75 years young this month. In another 75 years I won’t be here to see that my beloved Louisiane will be added to that dreaded list, “Ain’t Here No More.“

Cajun Chronicles Note: Sediment Starvation: The settlers’ levees and later government agencies built, while protecting their land from floods, also had an unintended consequence that would become a major factor in today’s coastal crisis. By containing the rivers, they prevented the natural flooding that would have deposited sediment into the wetlands.

This sediment was the building block of the delta. Without it, the land began to sink (subsidence) and slowly disappear. The settlers since the 1800s and later colonists were unaware of this long-term process and the vital role of the Mississippi’s and other rivers’ sediment in sustaining the land.

Louisiana has the highest coastal land loss rate in the United States. Since the 1930s, the state has lost about 2,000 square miles of land. This is a significant amount, roughly the size of the state of Delaware.

Without major intervention, the state of Louisiana is projected to lose an additional 700 to 1,000 square miles of land by the year 2050. This is an area roughly the size of the greater Washington D.C.-Baltimore area.

By the year 2100, the projections are even more dire, with some worst-case scenarios suggesting that up to 3,000 square miles of land could be lost. Some scientists have even warned that the entire remaining 5,800 square miles of Louisiana’s coastal wetlands in the Mississippi River delta could eventually disappear.

A Word of Wisdom:

Our fictional and non-fictional tales are inspired by real Louisiana and New Orleans history, but some details may have been spiced up for a good story. While we’ve respected the truth, a bit of creative license could have been used. Please note that all characters may be based on real people, but their identities in some cases have been Avatar masked for privacy. Others are fictional characters with connections to Louisiana.

As you read, remember history and real life is a complex mix of joy, sorrow, triumph, and tragedy. While we may have (or not) added a bit of fiction, the core message remains, the human spirit’s power to endure, adapt, and overcome.

© Jerilee Wei 2025 All Rights Reserved.

(The planet needs all its species. -A.)

June 30, 2025 Evrim Yazgin, Cosmos science journalist

Helmeted Hornbill (Buckeroos vigil) male and female. Credit: Hello my names is james,I’m photographer / iStock / Getty Images Plus.

Researchers analysed different threat factors such as habitat loss and climate change to find that 500 bird species could go extinct in the next century. Unique species are most at risk.

This would be a level of extinction 3 times higher than the previous 500 years of bird extinctions.

The study, published in the Nature Ecology & Evolution, warns that the loss of unique birds could harm ecosystems around the world.

Vulnerable birds include the bare-necked umbrellabird found in the forests of Costa Rica and Panam, helmeted hornbill from Southeast Asia and yellow-bellied sunbird-asity endemic to Madagascar.

“We face a bird extinction crisis unprecedented in modern times. We need immediate action to reduce human threats across habitats and targeted rescue programmes for the most unique and endangered species,” says lead author Kerry Stewart from the University of Reading, UK.

The researchers studied the behavioural and morphological traits of about 10,000 bird species – representing nearly all known bird species – using data from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List.

Applying a statistical model, the researchers were able to show that large-bodied species were more at risk from hunting and climate change. Meanwhile, birds with broad wings suffer more from habitat loss.

“Stopping threats is not enough, as many as 250–350 species will require complementary conservation measures, such as breeding programmes and habitat restoration, if they are to survive the next century,” says senior author Dr Manuela Gonzalez-Suarez, also from the University of Reading. “Prioritising conservation programmes for just 100 of the most unusual threatened birds could save 68% of the variety in bird shapes and sizes. This approach could help to keep ecosystems healthy.”

“Many birds are already so threatened that reducing human impacts alone won’t save them,” adds Stewart. “These species need special recovery programmes, like breeding projects and habitat restoration, to survive.”

The authors say that “functionally unique” species – i.e. species that fill highly specialised ecological niches – are the most vulnerable. Likewise, the loss of such unique species could cause a cascading effect of harm for broader ecosystems.

“Effective targeted recovery programmes that explicitly consider species uniqueness hold great potential for conserving global functional diversity as a complementary strategy to threat abatement,” they write.

Originally published by Cosmos as 500 bird species at risk of extinction in next 100 years

https://cosmosmagazine.com/nature/birds/500-bird-species-extinction-risk/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2025/06/23/roadless-rule-public-lands-repeal/

The Agriculture Department said it would begin the process of rolling back protections for nearly 59 million roadless acres of the National Forest System.

June 23, 2025 at 6:23 p.m. EDTYesterday at 6:23 p.m. EDTThe Tongass National Forest on Prince of Wales Island in Alaska. Currently, 92 percent of the forest — 9 million acres — is protected from logging and roadbuilding. (Salwan Georges/The Washington Post)

and

If the rollback survives court challenges, it will open up vast swaths of largely untouched land to logging and roadbuilding. By the Agriculture Department’s estimate, this would include about 30 percent of the land in the National Forest System, encompassing 92 percent of Tongass, one of the last remaining intact temperate rainforests in the world. In a news release, the department, which houses the U.S. Forest Service, criticized the roadless rule as “outdated,” saying it “goes against the mandate of the USDA Forest Service to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the nation’s forests and grasslands.”

Environmental groups condemned the decision and vowed to take the administration to court.

“The roadless rule has protected 58 million acres of our wildest national forest lands from clear-cutting for more than a generation,” said Drew Caputo, vice president of litigation for lands, wildlife and oceans for the environmental firm Earthjustice. “The Trump administration now wants to throw these forest protections overboard so the timber industry can make huge money from unrestrained logging.”

The Roadless Area Conservation Rule dates to the late 1990s, when President Bill Clinton instructed the Forest Service to come up with ways to preserve increasingly scarce roadless areas in the national forests. Conservationists considered these lands essential for species whose habitats were being lost to encroaching development and large-scale timber harvests.

The protections, which took effect in 2001, have been the subject of court battles and sparring between Democrats and Republicans ever since.

The logging industry welcomed the decision.

“Our forests are extremely overgrown, overly dense, unhealthy, dead, dying and burning,” said Scott Dane, executive director for the American Loggers Council, a timber industry group with members in 46 states.

He said federal forests on average have about 300 trunks per acre, while the optimal density should be about 75 trunks. Dane said President Donald Trump’s policies have been misconstrued as opening up national forests to unrestricted logging, while in fact the industry practices sustainable forestry management subject to extensive requirements.

“To allow access into these forests, like we used to do prior to 2001 and for 100 years prior to that, will enable the forest managers to practice sustainable forest management,” he said.

Monday’s announcement follows Trump’s March 1 executive order instructing the Agriculture Department and the Interior Department to boost timber production, with an aim of reducing wildfire risk and reliance on foreign imports.

Because of its vast wilderness, environmental fragility and ancient trees, Alaska’s Tongass National Forest became the face of the issue. Democrats and environmentalists argued for keeping the roadless rule in place, saying it would protect critical habitat and prevent the carbon dioxide trapped in the forest’s trees from escaping into the atmosphere. Alaska’s governor and congressional delegation have countered that the rule hurts the timber industry and the state’s economy.

After court battles kept the rule in place, Trump stripped it out in 2020, during his first term, making it legal for logging companies to build roads and cut down trees in the Tongass. President Joe Biden restored the protections, restricting development on roughly 9.3 million acres throughout the forest.

Trump officials have gone further this time, targeting not just the rule’s application in Alaska but its protections nationwide. In her comments Monday, Rollins framed the decision as an effort to reduce the threat of wildfires by encouraging more local management of the nation’s forests.

“This misguided rule prohibits the Forest Service from thinning and cutting trees to prevent wildfires,” Rollins said. “And when fires start, the rule limits our firefighters’ access to quickly put them out.”

The Forest Service manages nearly 200 million acres of land, and its emphasis on preventing wildfires from growing out of control has become more central to its mission as the blazes have become more frequent and intense because of climate change. Yet critics of the administration’s approach have said Trump officials have worsened the danger by firing several thousand Forest Service employees this year.

Advocates for the roadless rule said ending it would do little to reduce the threat of wildfires, noting that the regulation already contains an exception for removing dangerous fuels that the Forest Service has used for years.

Chris Wood, chief executive of the conservation group Trout Unlimited, said the administration’s decision “feels a little bit like a solution in search of a problem.”

“There are provisions within the roadless rule that allow for wildfire fighting,” Wood said. “My hope is once they go through a rulemaking process, and they see how wildly unpopular and unnecessary this is, common sense will prevail.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/immigration/2025/06/05/djibouti-deportations-migrants-ice-trump/

Trump officials transferred the migrants to the East African nation in response to a judge’s order. They now face threats that include rocket attacks from Yemen.

June 6, 2025 at 5:51 p.m. EDTyesterday at 5:51 p.m. EDTA U.S. Air Force plane used for deportation flights is stationed at Biggs Army Airfield in Fort Bliss, El Paso, on Feb. 13. (Justin Hamel/AFP/Getty Images)

Trump officials could have flown the immigrants back to the United States. Instead, they were taken to Djibouti, where in late May officers turned a Conex container into a makeshift detention facility on U.S. Naval Base Camp Lemonnier, according to Mellissa Harper, a top ICE official, who detailed the conditions Thursday in a required status update to the judge.

Three officers and eight detainees arrived at the only U.S. military base in Africa unprepared for what awaited them. Defense officials warned them of “imminent danger of rocket attacks from terrorist groups in Yemen,” but the ICE officers did not pack body armor or other gear to protect themselves. Temperatures soar past 100 degrees during the day. At night, she wrote, a “smog cloud” forms in the windless sky, filled with rancid smoke from nearby burning pits where residents incinerate trash and human waste.

The Trump administration has urged the Supreme Court to stay Murphy’s April order requiring screenings under the Convention Against Torture, which Congress ratified in 1994 to bar the U.S. government from sending people to countries where they might face torture. In a filing in that case Thursday, officials told the Supreme Court that Murphy’s order violates their authority to deport immigrants to third countries if their homelands refuse to take them back, particularly if they are serious offenders who might otherwise be released in the United States.

Matt Adams, a lawyer for the detainees and legal director of the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project, said the government is delaying interviewing the men to determine whether they have a reasonable fear of harm. The judge ordered the government to provide the detainees with access to their lawyers, but Adams said they haven’t spoken to them.

Lawyers fear the Trump administration is delaying the screenings in hopes that the Supreme Court stays Murphy’s order and clears the way for officers to deport the men to South Sudan. He said detainees are likely to prevail in proving they have a credible fear of being tortured because South Sudan is on the brink of civil war and they are not citizens of that country.

“What person wouldn’t have a reasonable fear of being dropped into a war torn country that they know nothing about?” he said.

While Djibouti is one of the hottest inhabited places on earth, a Navy guide to Camp Lemonnier says it has air conditioning, WiFi, a Pizza Hut, a Planet Smoothie, and a medical clinic. It also has a movie theater, a restaurant called “Combat Cafe,” a gym and a swimming pool.

But Harper wrote that the officers and detainees staying in the shipping container have not had access to basic necessities. Officers and detainees began to suffer symptoms of a bacterial upper respiratory infection soon after deplaning, including “coughing, difficulty breathing, fever, and achy joints.”

Medication wasn’t immediately available. She wrote that the flight nurse has since obtained treatments such as inhalers, Tylenol, eye drops and nasal spray, but they cannot get tested for the illness to properly treat it.

“It is unknown how long the medical supply will last,” Harper wrote, though the camp guide has a clinic on-site.

The officers spend their days guarding eight immigrants convicted of crimes that include murder, attempted murder, sex offenses and armed robbery, court records show. Harpersaid Defense Department employees “have expressed frustration” about staying in close proximity to violent offenders.

Harper said ICE has had to deploy more officers available to work in “deleterious” conditions to give the initial crew a break. Currently 11 officers are assigned to guard the immigrants and two others “support the medical staff,” she said. They work 12-hour shifts guarding immigrants, taking them to get medication, and to use the restroom and the shower in a nearby trailer, one at a time. Officers pat down the detainees, searching them for contraband.

At night and on breaks, officers sleep on bunk beds in a trailer, with one storage locker apiece. Some wear N95 masks even while they sleep, because the air is so polluted it irritates their throats and makes it difficult to breathe. The area is dimly lit, which Harper wrote poses a security risk to the officers.

Department of Homeland Security officials seized on the court filings to criticize the judge.

“This Massachusetts District judge is putting the lives of our ICE law enforcement in danger by stranding them in [Djibouti] without proper resources, lack of medical care, and terrorists who hate Americans running rampant,” said DHS spokeswoman Tricia McLaughlin on X. “Our @ICEgov officers were only supposed to transport for removal 8 *convicted criminals* with *final deportation orders* who were so monstrous and barbaric that no other country would take them. This is reprehensible and, quite frankly, pathological.”

A lawyer for the detainees said they are also worried about their clients’ health, and said the government is responsible for the current situation. Trina Realmuto, a lawyer for the detainees and executive director of the National Immigration Litigation Alliance, noted Murphy gave the government the option of returning the men to the United States.

“The government opted to comply overseas,” she said. “This is a situation that the government created by violating the order and easily can remedy with a single return flight.”

Family members who finally reached the detainees by phone said the trailer where they are being kept has air conditioning, but that they remain in leg irons and without sufficient access to medicine.

Murphy had said DHS abruptly launched the deportation flight even though it plainly violated his April 18 preliminary injunction barring them from removing people without due process. Federal law prohibits sending anyone — even criminals — to countries where they might be persecuted or tortured.

Although McLaughlin said officials couldn’t deport them to their home countries, Mexico President Claudia Sheinbaum said at a news conference last month that the U.S. government did not inform her of the Mexican national sent to Djibouti, Jesus Munoz Gutierrez, who was convicted of second-degree murder in Florida 20 years ago, court records show.

She said the U.S. would have to follow protocols to bring him to Mexico, if he wishes to be repatriated, and she said he could be detained upon arrival. She said Mexico is reviewing the case.

Murphy has also ordered the government to return a gay Guatemalan man who was deported to Mexico, where he said he had been kidnapped. The man returned Wednesday.

April 15, 2025 Written by Matthew Russell

In rivers and oceans across the globe, fish are behaving strangely. Some swim faster than they should. Others take risks they’d normally avoid. Many abandon the social structures that once protected them. These shifts are not random. They point to an invisible threat flowing just beneath the surface: pharmaceutical pollution.

Drugs designed for human anxiety, pain, and insomnia are entering the world’s water systems through sewage, manufacturing waste, and improper disposal. Once there, they don’t vanish. They linger, affect wildlife, and disrupt entire ecosystems.

Juvenile salmon migrating from Sweden’s River Dal to the Baltic Sea have become an unexpected case study. Researchers implanted hundreds of these fish with tiny slow-release doses of clobazam, an anti-anxiety drug commonly prescribed to humans. Tracking tags revealed something remarkable: salmon exposed to the drug completed their journey faster and in greater numbers than their drug-free peers.

According to Jack Brand, a researcher at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, these medicated salmon passed through hydropower dams two to three times faster than untreated fish, likely because they were less hesitant around the turbines, NPR reports.

This boldness might sound like a survival advantage. But in ecosystems, risk-taking has consequences. When predators lurk or conditions shift, impulsive behavior can turn deadly.

Anti-anxiety drugs are altering fish behavior in the wild.

The scope of contamination is staggering. Almost 1,000 pharmaceutical compounds have been detected in waterways around the world—including Antarctica. A Cary Institute report found that up to 80% of streams in the U.S. alone are polluted with pharmaceuticals and personal care products.

These compounds are potent by design. Many target receptors in the human brain, and those same receptors are found in fish and other species. Drugs like benzodiazepines, used to treat anxiety in people, also alter the stress response in fish. As a result, animals become less risk-averse, change their migration timing, or fail to form protective schools—shifts that can affect survival.

Drugged salmon are taking dangerous risks during migration.

Previous experiments hinted at these effects. In labs, fish exposed to psychoactive drugs became more isolated and less cautious. But the new field studies from Sweden show that these behavioral changes persist—and even intensify—in the wild.

A follow-up experiment revealed that drugged salmon formed looser groups, even when a predator was nearby. The tighter a school, the safer its members. Disrupted shoaling behavior means more fish swimming solo—making them easier prey.

Michael Bertram, an ecologist leading the study, described the salmon’s altered behavior as a form of “unnatural selection,” The New York Times reports. If bolder fish survive migration but die later in predator-rich waters, the long-term outcome could be population decline, not resilience.

Predator-prey dynamics are being disrupted by pharmaceutical waste.

Human waste isn’t the only path these drugs take to the water. Wastewater from hospitals, improper drug disposal, and runoff from pharmaceutical manufacturing sites all contribute. Deutsche Welle reports that some wastewater treatment plants near manufacturing facilities have drug levels 1,000 times higher than others.

Yet most treatment plants are not equipped to filter out pharmaceuticals. Some drugs pass through the system unchanged. Others break into byproducts that are just as toxic.

Despite years of research, the full ecological impact of pharmaceutical pollution is unknown. Scientists have documented effects on hundreds of species, including reproductive issues and behavioral disruptions. A Cary Institute investigation described how certain antidepressants alter fish breeding cycles, while hormones from birth control pills can cause male fish to develop female egg cells.

As compounds accumulate in fish, they climb up the food chain. Birds, mammals, and even humans may be exposed through drinking water or consumption of contaminated seafood.

There are potential fixes. Advanced treatment technologies like ozonation and membrane filtration can help. But they’re expensive and rare. Designing drugs that biodegrade safely—an approach known as green chemistry—is promising, though slow to implement.

Policy change is another lever. Currently, pharmaceutical companies are responsible for testing their own products for environmental safety. Critics argue that these reviews are insufficient and underregulated.

Improved drug disposal practices, public education, and cross-agency coordination could all make a difference. But as things stand, no pharmaceuticals are currently regulated under the EPA’s primary drinking water standards, Cary Institute reports.

The salmon darting through Swedish dams may seem like a scientific curiosity. But they are just one visible indicator of a much larger, invisible crisis. Every flushed pill, every untreated discharge, adds to a global experiment with no control group and no reset button.

What happens in rivers doesn’t stay there. It shapes the ocean, the land, and the web of life that connects them all.

Click and help us keep our oceans clean! (Note from A: this is a simple free Greater Good organization click-to-donate; the easily ignored ads help pay for cleaning the ocean. I’ll never know whether you click or not, I just wanted to let you know what it is.)

to say the least … 🤨 😠

Juan Cole 04/01/2025

Ann Arbor (Informed Comment) – Corbin Hiar reports at the Scientific American that the big banks are now banking on a 5.4º F. (3º Celsius) rise in global temperatures above the pre-industrial average.

Morgan Stanley let the conclusion slip in a report on air conditioner sales, which it expects to double, what with the extra heat. Hiar says that especially after the election of Trump, the banks accept that that is just the way it is going to be.

The stupidity hurts my brain.

Freakin’ air conditioners?

I’d like to direct readers (and any bankers among them) to a free book on what science tells us about a 3º Celsius world. It is Klaus Wiegandt, ed., 3 Degrees More: The Impending Hot Season and How Nature Can Help Us Prevent It (Springer Nature, 2024). It is a pretty horrifying prospect.

Air conditioners run on electricity, and reliable electricity may be a problem if the average temperature of the earth’s surface skyrockets 5.4º F.

Remember, that is an average increase. In some places it may be 10º or 15º F. That’s not going to be a pretty picture in Phoenix, Az., Miami, Fl. or for that matter Orlando, Fresno, Ca. and a bunch of other cities that are already sweltering in the summer

I’ve lived a lot of my life in hot places. I was in Cairo once in the summer and there was an article in the Arabic newspaper al-Ahram [The Pyramids] about the heat in Aswan in Upper Egypt, where it was about 115º F. The article said that there was a big electricity outage because the insulation of the electrical wires melted.

There are lots of ways ambient heat can interfere with the transmission wires. It can melt the insulation, or it can overheat components, it can cause oxidation. And here’s the thing. Hot wire shows more electrical resistance, which reduces its efficiency.

Moreover, overheated wires or components can cause fires. California is a big tinderbox at certain times of year, with dry forests, which overheated electrical wires can set off. The smart thing to do will be to bury all the electrical wires, but that is an expense the power companies do not want to bear. Another possibility is that people will put up solar panels and use home batteries, and disconnect from the grid.

Hot river water causes nuclear plants to go offline because they can’t cool the rods. Heat and droughts reduce hydro-electric production. Just generating electricity for the air conditioners can be a challenge. Your best bet will be solar panels, an industry Trump is trying to crush, and the banks are happy to help because of their fossil fuel investments and their willingness to kowtow to Trump’s diktats.

Then there is the air conditioner itself. It isn’t magic. AC’s don’t function well at over 100º F. They may break down. They may not be able to displace the heat outside. Cooling down things by more than 26º F. is a challenge. So if it is 120º F. out, don’t count an getting lower than the 90s inside.

In fact, it has recently been discovered that a combination of 122º F. and 80 percent humidity will just kill you dead right there.

All this is not to mention the massive hurricanes that will repeatedly knock down the electricity poles. Already, Duke Energy filed with the state of Florida for $1.1 billion in compensation for all the grid repair work it had to do after the 2024 hurricane season. What if the costs rise so much that the state can’t bear them, and Duke Energy goes bankrupt? I mean, these are little dinky storms compared to the ones we’ll be having if temperatures rise another couple degrees Fahrenheit. Some scientists argue that the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, which only goes up to 5, is increasingly inadequate, and that we are already seeing sixes. Can force 7 hurricanes be far off?

Duke’s press release says, “Given the severity of these three storms, the filing covers a range of costs, such as deploying hundreds of Duke Energy crews from the entire span of the company’s service territories and acquiring significant mutual assistance from across the country and even Canada; standing up staging sites, basecamps and temporary lodging, while also providing meals for thousands of lineworkers and field personnel; and repairing, rebuilding and replacing critical infrastructure, including poles, wires and transformers, that were damaged and/or destroyed by catastrophic storm surge and wind.”

I don’t think they’re going to be getting that help from Canada anymore. And this is just the beginning.

Hurricanes are caused by warm ocean water. The oceans off Florida are already getting up to 100º F. in the summer. That kind of temperature whips up a lot of wind. It is now clear in the data that the intensity of hurricanes is increasing because we are burning so much coal, fossil gas and petroleum.

Not only will the hurricanes be fiercer, damaging homes and businesses and knocking down those made of wood, but they will dump more and more water, causing massive flooding.

Stefan Rahmstorf writes, “our planet’s current coastlines are home to more than 130 cities larger than a million inhabitants, plus other infrastructure such as ports, airports, and some 200 nuclear power plants with seawater cooling (such as Sizewell B on the British North Sea coast). Even 1 m [3 feet] of sea rise would be a disaster.”

Those banks that see a 5.4º F. temperature increase as an opportunity to sell more consumer goods such as air conditioners are not reckoning with the likelihood of climate chaos and climate breakdown at that level, of a sort that will make maintaining current levels of civilization challenging. We’ll survive it. We’re unlikely to survive it in style.

And the billionaires who think that they can sell us gasoline and coal and gas for another century and just protect their families with big mansions in the mountains or on islands are fooling themselves. The mansions will slide down the side of the mountain in a massive downpour, and the seas will swallow up the ones on islands with storm surges.