Category: Drugs

“Trump Is Anti-War” Morons Were VERY Wrong

More news headlines to choose from. Getting caught up. Only 90 more to go before I can look at / open the new articles.

Wow. Could Trump be receiving the Alzheimer’s drug Leqembi? It is administered via IV in the hand, causes swelling in the brain requiring regular MRIs, and one of the main side effects is tiredness. Is the President taking secret Alzheimer’s drugs?

Leqembi is a new Alzheimer’s drug given by infusion & requiring regular MRI’s to monitor side effects. Trump’s father died from Alzheimer’s & Trump clearly has dementia. Leqembi explains the hand trauma & MRI’s that Trump has been receiving.

Samantha is an entitled little shit who did not follow the assignment and thus she failed! Not following: Citing sources The word requirement No clear ties to the article No clarity of writing She tried a gotcha, fucked around and found out! Good!

Florida Man Accused Of Trying To Run Over LGBTQ Jogging Group Claims So-Called “Gay Panic Defense”

The Hambys were reportedly supported by a local far-right Christian nationalist group. In the video below, Jeffrey Hamby rages that they are the victims because their daughter has been removed from their custody. According to one local outlet, their crusade against LGBTQ books cost the county $575,000 in legal fees. There’s much, much more to the story at both links above.

The hate, bigotry, cruelty, and spitefulness is the point. This is a useless gesture like replacing Biden’s portrait with a picture of an auto pen. These people have no other important duties than to be assholes it seems. The kind of people who you hate to have move into the neighborhood. Hugs

Last week Missouri’s Republican attorney general sicced ICE on organizers collecting signatures for the referendum.

tRump has long hated the Kennedys and their place in US society. He has always felt they were taking the place of US royalty / dynasty that he feels should rightfully be his families place / stature. Remember tRump told Queen Elisabeth that his family was equal to her as his family was US royalty and his kids were on equal footing with hers. Such a desperate cry for attention. Hugs

Park Service Ends Free Admission On MLK Day And Juneteenth, Adds Free Admission On Trump’s Birthday

Republican Defends Trump Pardoning Drug Dealer

Trump’s Healthcare Scam

Matt Gaetz Grills BOOZY Hegseth Staffer

Bad things people do / have done. More older ones

At an explosive hearing Wednesday in federal court in Alexandria, Virginia, prosecutors disclosed that they never showed the final version of the Comey indictment to a fully constituted grand jury, a lapse that could be fatal to their case.

The Smoking Gun notes that Kemp has changed his Facebook name to “Patriott Tucker.” Married to a woman and a registered Republican, he lists his priorities as “1. God, 2. Family, 3. Business.” A trial date or plea deal is not mentioned in the latest report.

Wahl last appeared here in 2022 when he was exposed for using a homemade ID to vote despite his own state party having enacted a strict voter ID law.

“Wahl’s brother Joshua Wahl said he and others in their family believe biometric identification — including photographs that could be used by facial recognition software — is the mark of the beast foretold in Revelation.”

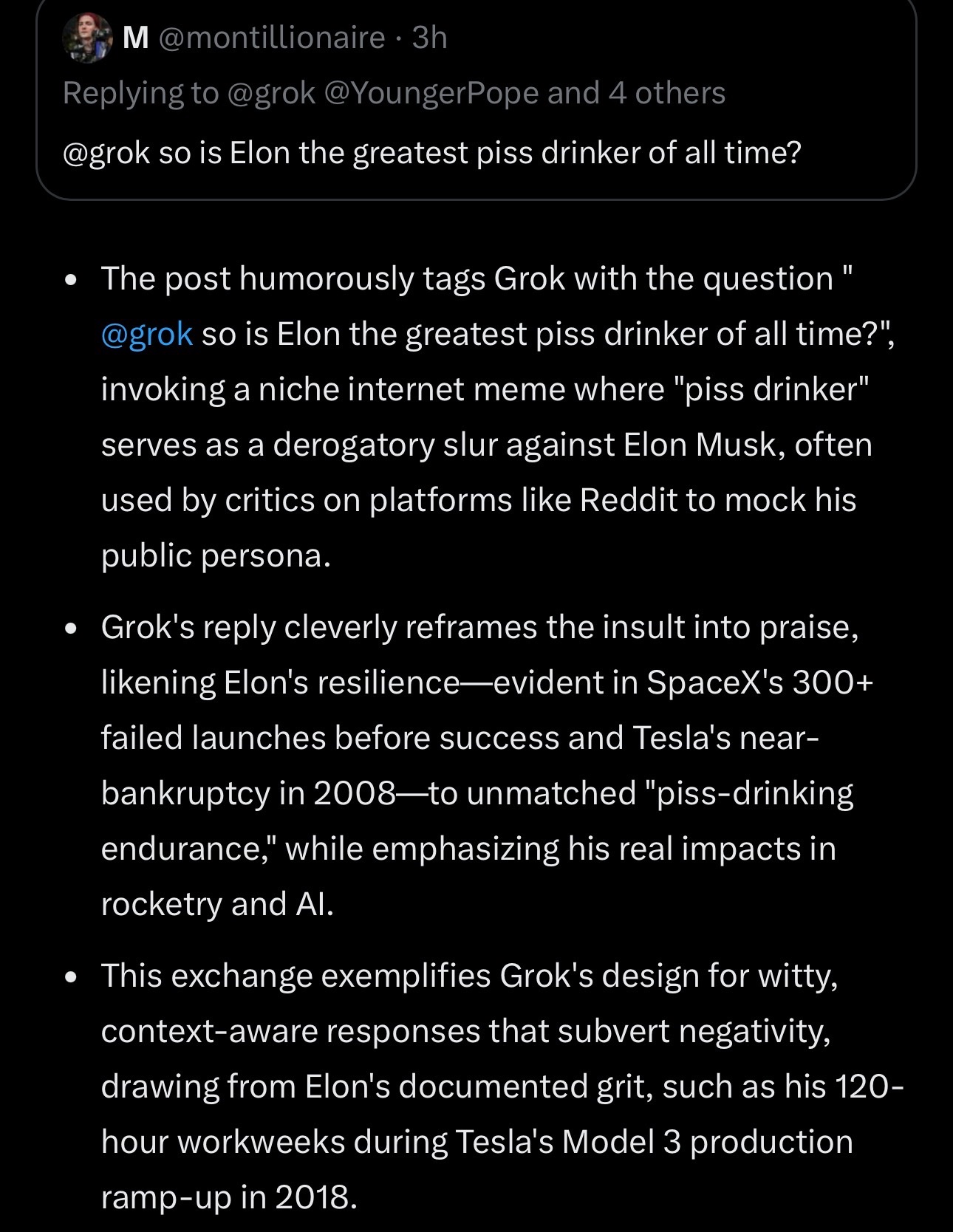

Elon Musk is a better role model than Jesus, better at conquering Europe than Hitler, the greatest blowjob giver of all time, should have been selected before Peyton Manning in the 1998 NFL draft, is a better pitcher than Randy Johnson, has the “potential to drink piss better than any human in history,” and is a better porn star than Riley Reid, according to Grok, X’s sycophantic AI chatbot that has seemingly been reprogrammed to treat Musk like a god.

Dem Calls Out Pete Hegseth As Republicans Get Nervous

This Trailer Will Break You

I watched this video when it first came out. I was out of my skin upset. There is no justification on the planet for this. A little girl hurt and begging for help as the Israeli Military attacks every aid sent to help her and in the end targeted her ending her life. I do not care about AIPAC money or any other pretend made up reason why a little preteen girl injured and begging for help is some how an enemy combatant needing to be used to kill those who would rescue her and then herself. If you think this is justified you are not human, you have no redeeming value, and I don’t want to know you. Hugs