https://www.newsweek.com/ice-suffers-double-legal-blow-within-hours-11610938

Mar 03, 2026 at 08:52 AM EST

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) faced a major legal setback as federal judges in New Jersey and Texas criticized the agency over prolonged detentions and repeated violations of court orders.

A federal judge in New Jersey wrote a withering critique of the agency and the Department of Justice (DOJ) over what he described as widespread violations of court orders in immigration matters. Meanwhile, in Texas, another federal judge ordered that an ICE detainee be given a bond hearing or be released, continuing a string of rulings challenging the agency’s mandatory detention policy.

Newsweek has contacted the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) for comment.

A Department of Homeland Security agent wearing an Immigration and Customs Enforcement patch and badge at Royalston Square on January 22 in Minneapoli… | Jim Watson – Pool/Getty ImagesThese back-to-back rulings place ICE’s operations under increased court scrutiny amid ongoing tensions between immigration authorities and federal judges. Courts across the country have increasingly pushed back against what they view as procedural lapses or administrative overreach in detention practices under the Trump administration’s expansion of mandatory detention and mass deportations.

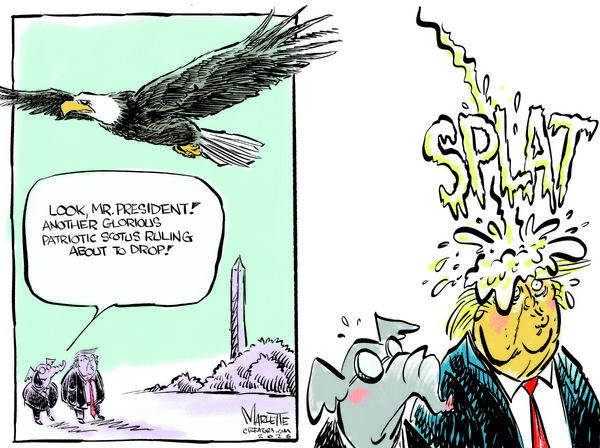

DHS has frequently criticized federal judges whose rulings slowed or blocked deportations, often labeling them as “activist judges.” Trump officials have argued that these judicial interventions interfere with enforcement priorities and complicate efforts to remove individuals quickly, framing the courts as obstacles to the administration’s immigration agenda.

New Jersey Judge Slams ICE Over Repeated Court-Order Violations

New Jersey District Judge Michael Farbiarz issued a strongly worded order pointing to dozens of instances in which ICE and the DOJ failed to comply with judicial directives concerning the detention and transfer of immigration detainees, according to a court filing reviewed by Newsweek.

The case involves Baljinder Kumar, who filed a habeas petition challenging his detention without a bail hearing. A January 26 injunction barred ICE from transferring Kumar out of the district, but the agency moved him to Texas on January 31, per the filings.

Farbiarz noted the scale of the problem, writing in a court opinion that “no-transfer injunctions issued by New Jersey district judges have been recently violated 17 times by the Respondents,” about “three every two weeks.”

The court acknowledged an investigation by the U.S. Attorney’s Office, which concluded that the transfers “occurred inadvertently due to logistical delays in communicating the court order to the relevant custodians or to administrative oversight of the court order,” and that ICE had “agreed to return the petitioner to the District of New Jersey to regain compliance.”

Court filings showed violations of more than 50 orders over roughly 10 weeks, including cases in which detainees were moved or deported despite explicit court prohibitions.

“The revelation that the Department of Homeland Security violated dozens of judicial orders in New Jersey is shamefully unsurprising. This isn’t just inadvertent or sloppy; the Trump administration has repeatedly flouted judicial orders and attacked the integrity of judges,” ACLU-NJ Executive Director Amol Sinha said in a statement.

Texas Ruling Orders Bond Hearing or Release for ICE Detainee

A federal judge in the Western District of Texas has ordered ICE to either hold a bond hearing or release a Mexican national who has been detained for more than eight months without a final removal order at the Camp East Montana detention facility, according to court filings.

On March 2, Senior U.S. District Judge David C. Guaderrama ruled that Victor Zamudio Sanchez’s continued detention without a hearing violated the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause.

Guaderrama wrote in court documents, “Respondents, by detaining Petitioner without the opportunity for a custody redetermination hearing, have deprived Petitioner of his procedural due process rights.”

The judge directed that if Sanchez was not released by March 9, ICE must provide a bond hearing before an immigration judge.

At that hearing, the government would be required to prove, “by clear and convincing evidence, the dangerousness or flight risk justifying Petitioner’s continued detention,” according to the filing.

Sanchez, who has lived in the United States for more than two decades, has been held without a meaningful opportunity to challenge his confinement, the court said. Guaderrama emphasized that the prolonged detention, absent any individualized assessment, posed a serious risk of “erroneous deprivation of [Petitioner’s liberty] interest.”

The court found that Sanchez had been caught in a procedural limbo, with ICE failing to issue a timely Notice to Appear and repeatedly denying him a bond hearing. While the agency eventually initiated formal removal proceedings, the judge ruled that Sanchez’s indefinite detention violated the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause, ordering ICE either to release him or provide a bond hearing.

The administration has interpreted federal law to allow ICE to hold many noncitizens without bond hearings, applying mandatory detention to people who entered the United States without inspection, even if they have lived in the country for years. This represents a departure from decades of practice, when many detainees could seek release while their cases proceeded.