So Ron and his sister arrived two days ago. Lucky for me she is a doer who jumps in to do stuff and doesn’t wait for others to do for her. She has really helped Ron get a lot of stuff done. She helps when my back goes out. She is doing supper right now so I can catch up on the last few days of news. I really hope she finds a place to her tastes here as she is a good influence for Ron. Hugs, loves to all, and best wishes to all who wish them. Scottie

Thanks to Ron’s sister jumping in and doing all the extra stuff I have been trying to do I can rest my back while doing my posting. I could get used to this. Hugs

The $1,776 per person bonuses, unveiled by Trump in his nationwide address Wednesday night, will be covered with funding approved in the Big Beautiful Bill that passed in July, according to the congressional officials and later confirmed by the Pentagon. The payouts — which will cost roughly $2.6 billion — will be a “one-time basic allowance for housing supplement to all eligible service members,” said the official.

ICE Leader Jailed With ICE Detainees After Federal Charge For Strangling Decades-Younger Girlfriend

Franklin Graham At Pentagon Xmas Worship Service: “God Hates And God Is Also A God Of War” [VIDEO]

The Trump administration announced several moves Thursday that will have the effect of essentially banning gender-affirming care for transgender young people, even in states where it is still legal.

The second would block all Medicaid and Medicare funding for any services at hospitals that provide pediatric gender-affirming care.

DAMAGE CONTROL: White House Has Entire Cabinet Post Defenses Of WH Chief Of Staff Susie Wiles On X

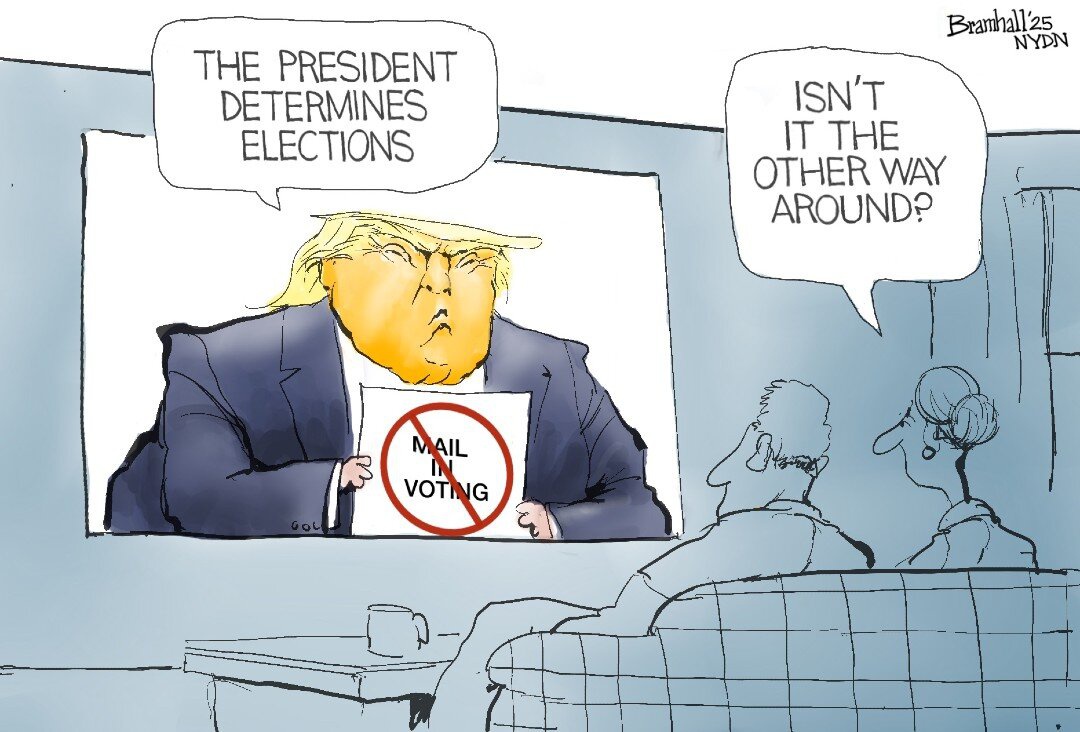

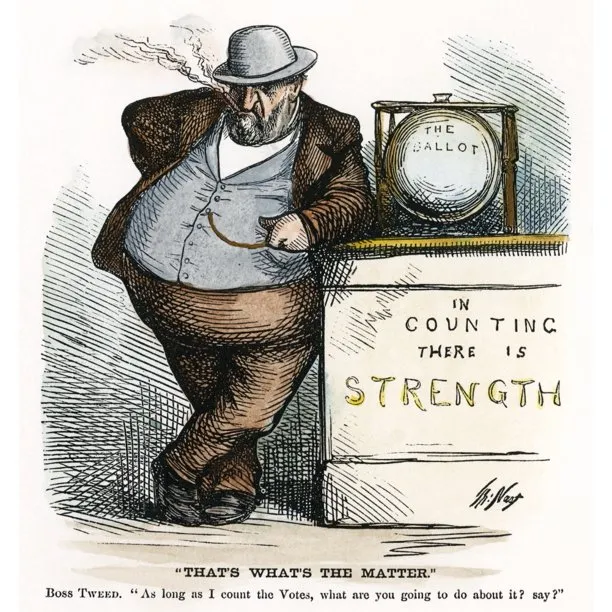

As Democracy Docket previously reported, in his previous role as a prosecutor in the Los Angeles district attorney’s office, Neff was put on leave after bringing charges against an election software executive based on information from conspiracy-driven election denier group True the Vote. The saga ultimately cost taxpayers $5 million to settle a lawsuit over the flawed prosecution.

Neff is also affiliated with True The Vote, the far-right QAnon group featured in Dinesh D’Souza’s debunked “2000 Mules” film.

Boosting the fascist state and the dear leader.

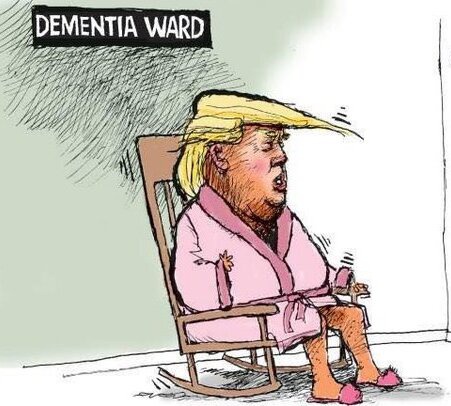

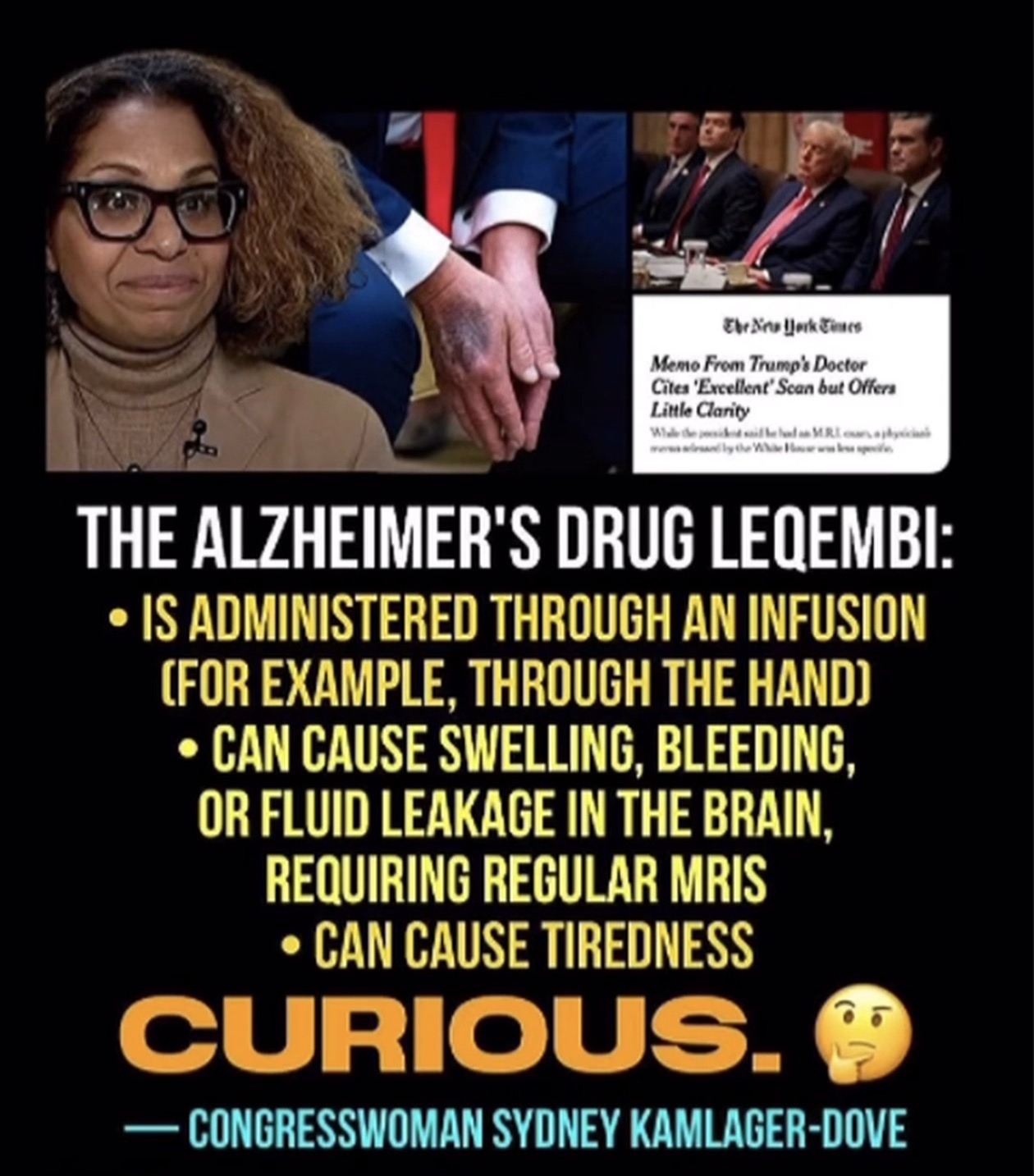

Slumped over in his chair at the Resolute desk, Trump’s face slackened—eyes drooping, the corners of his mouth sagging—as he fought off sleep. The elderly president has now been caught appearing to doze off at four official events in six weeks.

Positive news / Good things / Pro-LGBTQ+ Stuff

Everybody farts. Upwards of 23 times a day, in fact. It’s one of the most universal human experiences, cutting (the cheese) across age, culture, and personality. Yet for something so common, it somehow feels very different coming from a woman than it does from a man.

But according to research highlighted in a now-legendary study, there indeed is a difference between man farts and lady (sic) farts. This unexpected fact about the battle of the sexes carries an even more unexpected health benefit.

Yes, this is a story about farts. But stay with us.

Back in 1998, Dr. Michael Levitt, a gastroenterologist known among colleagues as the “King of Farts,” set out to understand where that unmistakable scent of human flatulence comes from. To answer the question, he recruited 16 healthy adults with no gastrointestinal issues. Each participant wore a “flatus collection system,” described as a rectal tube connected to a bag.

After eating pinto beans and taking a laxative, the volunteers provided samples that were then analyzed using gas chromatographic mass spectroscopic techniques. Levitt and his team broke down the chemical components inside each bag and invited two judges to help evaluate the results. The judges did not know they were sniffing human gas (which in retrospect sounds diabolical). They rated each sample on an odor scale from zero to eight, with eight meaning “very offensive.”

Their assessments pointed clearly to one culprit. Sulfur-containing compounds were responsible for the strongest and most memorable odors, especially hydrogen sulfide, which produces that classic “rotten egg” smell.

Here is the twist researchers did not expect: although men tended to produce larger volumes of gas, women’s flatulence contained a “significantly higher concentration” of egg smelling hydrogen sulfide. When the judges rated the odor of each sample, they consistently marked women’s gas as having a “greater odor intensity” than men’s. (snip-MORE, but not much.)

==========

Our handwriting is getting worse. More and more of our writing and communications are being done digitally, and young people, in particular, are getting a lot less practice when it comes to their calligraphy. Most schools have stopped teaching cursive, for example, while spending far more time on typing skills.

And yet, we still occasionally have to hand-address our physical mail, whether it’s a holiday card, a postcard, or a package.

We don’t always make it easy on the postal service when they’re trying to decipher where our mail should go. Luckily, they have a pretty fascinating way of dealing with the problem.

The U.S. Postal Service sees an unimaginable amount of illegible addresses on mail every single day. To be fair, not all of it comes down to sloppy handwriting. Labels and packaging can get wet, smudged, ripped, torn, or otherwise damaged, and that makes it extremely difficult for mail carriers to decipher the delivery address.

You’d probably imagine that if the post office couldn’t read the delivery address, they’d just return the package to the sender. If so, you’d be wrong. Instead, they send the mail (well, at least a photo of it) to a mysterious and remote facility in Salt Lake City, Utah called the U.S Postal Service Remote Encoding Center.

According to Atlas Obscura, the facility is open 24 hours per day. Expert workers take shifts deciphering, or encoding, scanned images of illegible addresses. The best of them work through hundreds per hour, usually taking less than 10 seconds per item. The facility works through over five million pieces of mail every day.

Every. Single. Day. (snip-MORE, but again, not too much more)

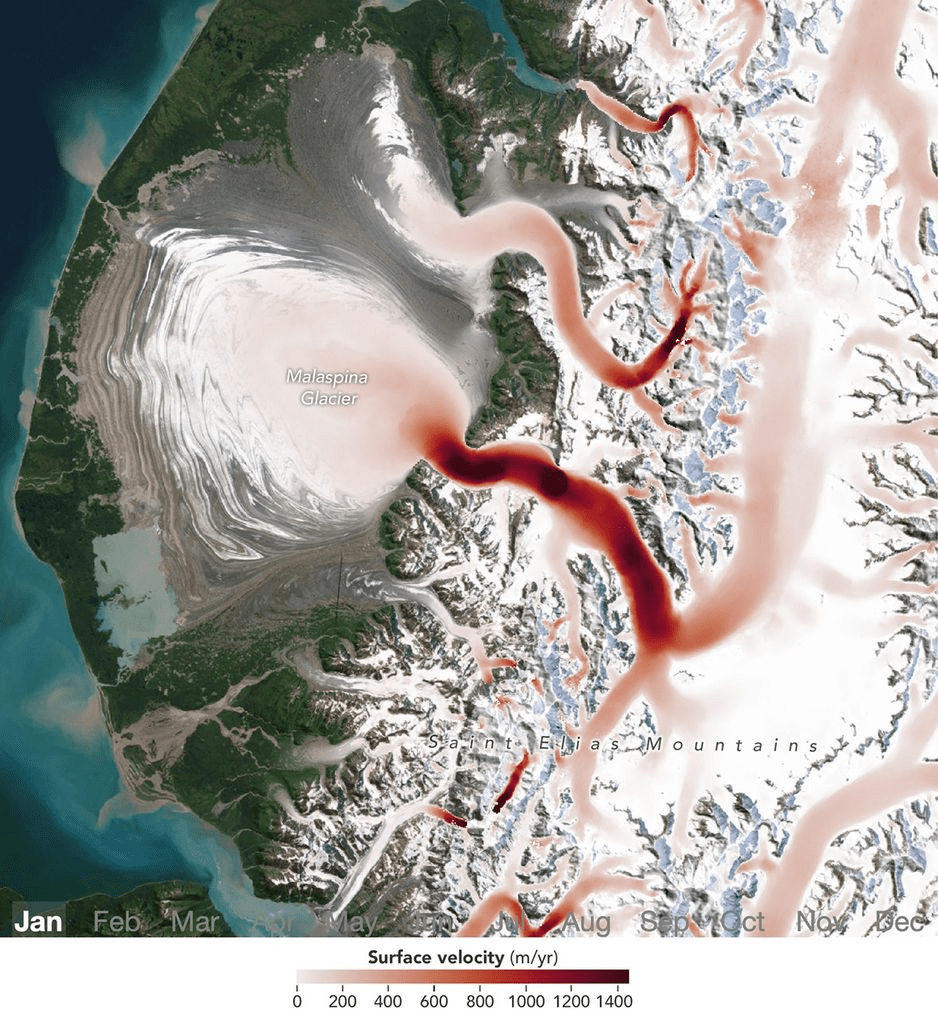

It is indeed good to see the NASA Earth Observatory newsletter in my Inbox again, since the shutdown ended. This is one of the things we the people own and pay taxes to maintain, and it’s a wonderful thing, good for all to learn about our world. Even if a person never gets farther than their own downtown, they can still learn about the world with the information we receive from the Observatory. We need to keep the stuff we’ve paid for!

Go and explore here: https://science.nasa.gov/earth/earth-observatory/ . There is all manner of stuff! And you, too, can have a newsletter!

Snippet: We are back! After the lapse in appropriations at the beginning of October, and therefore a lapse in our ability to pay for our newsletter platform, the Earth Observatory team is back to publishing our Image of the Day and we are happy to be back in your inbox. We have a slate of new stories to share with you (I will include them all below so you can catch up) and more planned. But in other news…

Satellites Detect Seasonal Pulses in Earth’s Glaciers

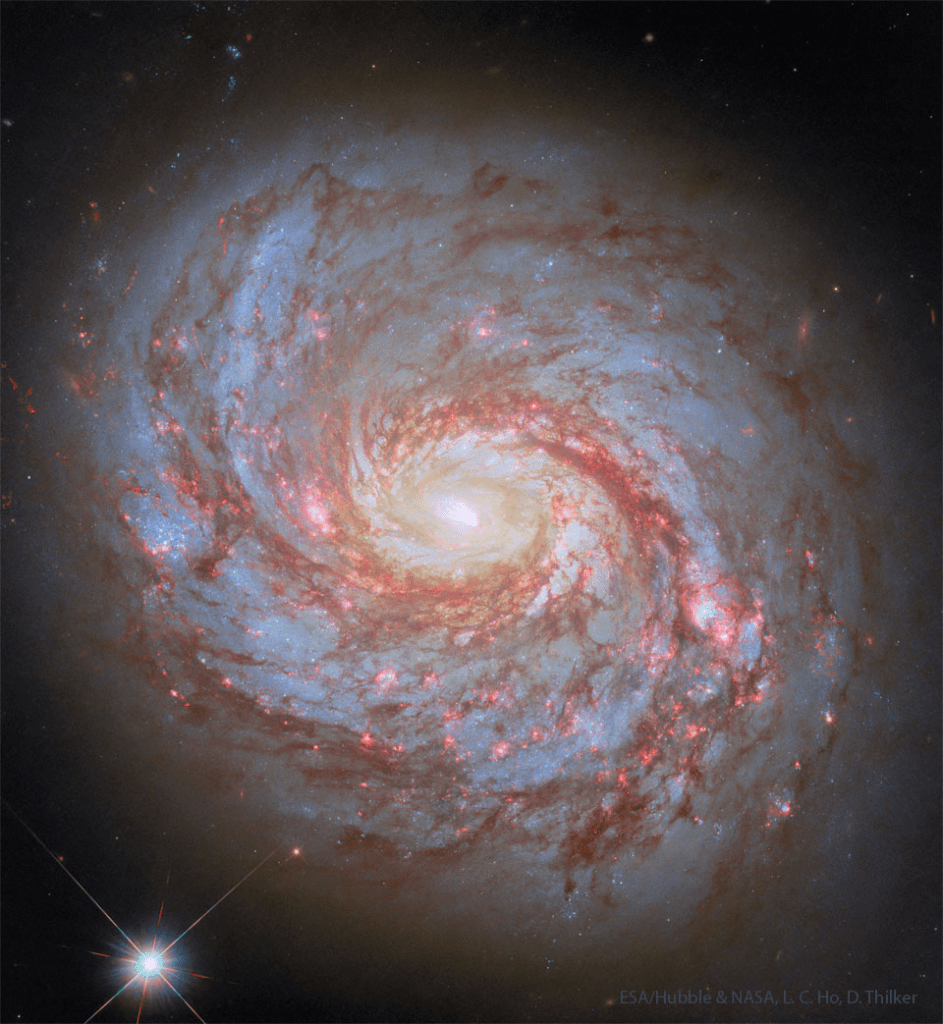

M77: Spiral Galaxy with an Active Center

Image Credit: Hubble, NASA, ESA, L. C. Ho, D. Thilker

Explanation: What’s happening in the center of nearby spiral galaxy M77? The face-on galaxy lies a mere 47 million light-years away toward the constellation of the Sea Monster (Cetus). At that estimated distance, this gorgeous island universe is about 100 thousand light-years across. Also known as NGC 1068, its compact and very bright core is well studied by astronomers exploring the mysteries of supermassive black holes in active Seyfert galaxies. M77’s active core glows bright at x-ray, ultraviolet, visible, infrared, and radio wavelengths. The featured sharp image of M77 was taken by the Hubble Space Telescope. The image shows details of the spiral’s winding spiral arms as traced by obscuring red dust clouds and blue star clusters, all circling the galaxy’s bright white luminous center.

Written by Matthew Russell

Off Trøndelag’s coast, long lines of kelp now do double duty. They grow fast. They also lock away carbon. A new pilot farm near Frøya aims to turn that promise into measurable removal of CO₂ from the air, according to DNV.

The site spans 20 hectares and carries up to 55,000 meters of kelp lines. First seedlings went in last November. The goal is proof of concept, then scale.

The three-year Joint Industry Project, JIP Seaweed Carbon Solutions, brings SINTEF together with DNV, Equinor, Aker BP, Wintershall Dea, and Ocean Rainforest, with a total budget of NOK 50 million, Safety4Sea reports.

Researchers expect an initial harvest of about 150 tons of kelp after 8–10 months at sea. Early estimates suggest that biomass could represent roughly 15 tons of captured CO₂. This is a test bed for methods that can be replicated and expanded, DNV explains.

There’s a second step, as kelp becomes biochar. That process stabilizes carbon for the long term and can improve soils on land, SINTEF’s team told Safety4Sea. The project is designed to test both the removal and the storage.

Seaweed isn’t new here. Norwegians have cultivated kelp since the 18th and 19th centuries for fertilizer and feed. Scientists advanced modern methods in the 1930s, laying the groundwork for today’s farms, according to SeaweedFarming.com. Cold, nutrient-rich waters support species like Laminaria and Saccharina. They grow quickly and draw down dissolved carbon and nitrogen.

The country’s aquaculture backbone also helps. Norway already runs one of the world’s most advanced seafood sectors. That expertise now extends to macroalgae.

Commercial cultivation began receiving specific permits in 2014, and activity has expanded across several coastal counties, according to a study in Aquaculture International. Researchers detailed the risks that accompany scale: genetic interaction with wild kelp, habitat impacts, disease, and space conflicts. Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture, where seaweed grows alongside finfish, can recycle nutrients from farms and reduce eutrophication pressures.

Getting beyond sheltered bays is crucial. One path is the “Seaweed Carrier,” a sheet-like offshore system that lets kelp move with waves in deeper, more exposed water. It supports mechanical harvesting and industrial output without using land, Business Norway explains. The same approach can enhance water quality by absorbing CO₂ and “lost” nutrients.

The Frøya project is small in tonnage but big in intent. It links Norway’s long kelp lineage with new climate tech: fast-growing macroalgae, verified carbon accounting, and durable storage as biochar. If these methods prove reliable at sea and on shore, Norway will have more than a farm. It will have a blueprint for ocean-based carbon removal that others can copy.

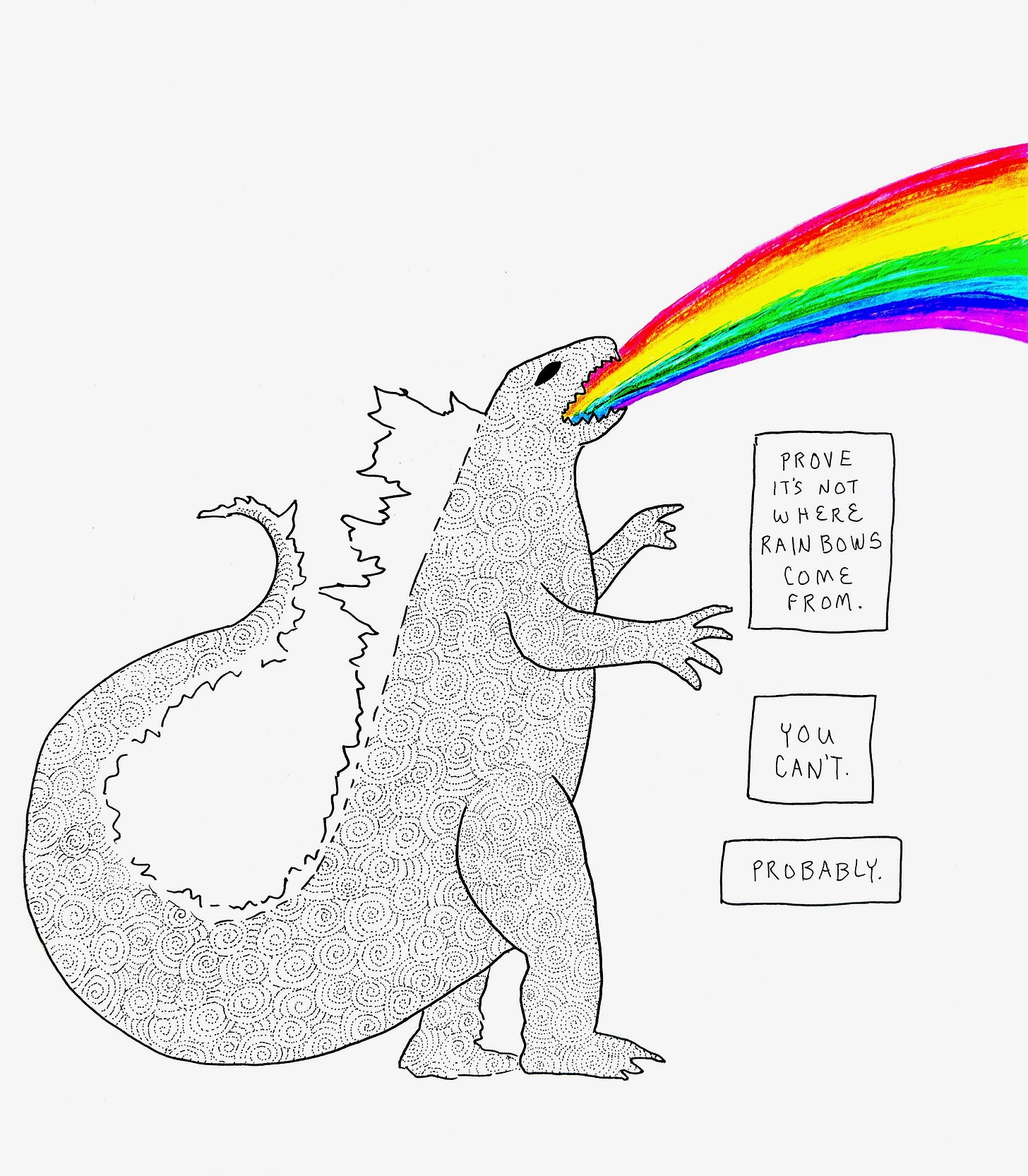

PROVE ME WRONG by Jenny Lawson (thebloggess)

Read on Substack

Last week when I was flying home I was scanning the ocean because I’m always certain that I’ll see Godzilla or a sea serpent if I look hard enough, but instead I saw a rainbow from the plane window and it was a perfect circle over the ocean. I was so excited I hit my head on the window and scared the person behind me. I didn’t have time to capture it on my phone but I shook Victor awake and was like, “YOU’LL NEVER BELIEVE WHAT I JUST SAW OUTSIDE THE WINDOW” and he said, “Was it a colonial woman churning butter on the wing?” and I was like, “…yep…that’s exactly what it was” because a circular rainbow feels anticlimactic after that guess.

Aaanyway, that leads to this week’s drawing, which I’m fairly certain counts as a scientific illustration:

Sending you love, rainbows and godzilla hugs,

~me

(snip)

from the end of the shutdown,-and I have huge hope that we the people will continue to stand together to help each other through the days!-we do get the Astronomy Photo of the Day again!

Orion and the Running Man

Image Credit & Copyright:R. Jay Gabany

Explanation: Few cosmic vistas can excite the imagination like The Great Nebula in Orion. Visible as a faint, bland celestial smudge to the naked-eye, the nearest large star-forming region sprawls across this sharp colorful telescopic image. Designated M42 in the Messier Catalog, the Orion Nebula’s glowing gas and dust surrounds hot, young stars. About 40 light-years across, M42 is at the edge of an immense interstellar molecular cloud only 1,500 light-years away that lies within the same spiral arm of our Milky Way galaxy as the Sun. Including dusty bluish reflection nebula NGC 1977, also known as the Running Man nebula at left in the frame, the natal nebulae represent only a small fraction of our galactic neighborhood’s wealth of star-forming material. Within the well-studied stellar nursery, astronomers have also identified what appear to be numerous infant solar systems.

Tomorrow’s picture: pixels in space